Pathoanatomy and Pathophysiology

of Chronic Low Back Pain

and Chiropractic Care

Six years later, in 1986, prescribing opiates for chronic pain was further enhanced when physicians Russell Portenoy, MD, and Kathleen Foley, MD, published a small case series (38 subjects) that concluded that chronic opioid analgesic use was safe in patients with no history of drug abuse (5).

By 2017, America’s opioid crisis had escalated to claiming (killing) 64,000 Americans yearly (6). Yet, it was in the same year (2017) that the first randomized clinical trial to evaluate the effectiveness of opioids for pain was completed and published (7). It appeared in the Journal of the American Medical Association and was titled:

Effect of Opioid vs Non-opioid Medications

on Pain-Related Function in Patients

With Chronic Back Pain or Hip or Knee Osteoarthritis Pain:

The SPACE Randomized Clinical Trial

The objective of this study was to compare opioid drugs v. the non-opioid drugs (NSAIDs, acetaminophen) over 12 months on pain-related function, pain intensity, and adverse effects.

The study involved 234 subjects who were suffering from moderate to severe chronic back pain or hip or knee osteoarthritis pain. Chronic pain was defined as pain nearly every day for 6 months or more. The authors made these comments:

“Rising rates of opioid overdose deaths have raised questions about prescribing opioids for chronic pain management.”

“Because of the risk for serious harm without sufficient evidence for benefits, current guidelines discourage opioid prescribing for chronic pain.”

“Pain intensity was significantly better in the non-opioid group over 12 months.”

“Adverse medication-related symptoms were significantly more common in the opioid group.”

“Treatment with opioids was not superior to treatment with non-opioid medications for improving pain-related function over 12 months.”

“This study does not support initiation of opioid therapy for moderate to severe chronic back pain or hip or knee osteoarthritis pain.”

“Among patients with chronic back pain or hip or knee osteoarthritis pain, treatment with opioids compared with non-opioid medications did not result in significantly better pain-related function over 12 months.”

“Opioids caused significantly more medication-related adverse symptoms than non-opioid medications.”

“Overall, opioids did not demonstrate any advantage over non-opioid medications that could potentially outweigh their greater risk of harms.”

“Studies have found that treatment with long-term opioid therapy is associated with poor pain outcomes, greater functional impairment, and lower return to work rates.”

As a consequence of the escalating awareness of the hazards of using opioids for pain and the lack of their effectiveness, physician groups, government agencies, and society began an all-out effort to curtail their use. These efforts increased upon realizing that opioid’s propensity for causing addiction resulted in many Americans transitioning to illegal narcotics (heroin, fentanyl, etc.) Eighty percent of heroin addicts in America were first given a physician prescribed opioid for pain (8).

Sadly, for a variety of reasons, these curtailment efforts have not worked. Opioid related deaths rose from 64,000 in 2017 to 72,000 in 2019 to more than 93,000 in 2020. The increase from 2019 to 2020 alone represents a 30% increase in a single year (6, 9, 10).

Adding to the dilemma of using pharmacology to manage pain is an article that appeared in the November 2021 issue of Scientific American, titled (11):

Painkiller Risks Advil, Tylenol and the Like

—Increasingly Used to Replace Opioids—

Have Downsides

The article profiles how the chronic use of nonsteroidal drugs (NSAIDs), such as ibuprofen (Motrin, Advil) are coupled with an increased risk of gastrointestinal bleeding, heart attacks, heart failure, strokes, vascular clotting, fluid retention, and kidney damage.

Acetaminophen (Tylenol) is found in more than 600 consumer products. “In the United States, acetaminophen poisoning has displaced hepatitis as the most common reason people need a liver transplant.”

The author states:

“There is no such thing as a risk-free drug, and that goes for our most trusted painkillers.”

“Everything we put inside us carries some risk. There’s no free lunch.”

Acknowledging this crisis, health policy makers have insisted on the vetting of non-drug alternatives for the management of pain, insisting that the assessments should only include approaches that “have sufficient evidence to suggest their potential value” (12). The first such approach they advocated was chiropractic care.

The largest modern review of the chiropractic profession was published in the journal Spine in December 2017, and titled (13):

The Prevalence, Patterns, and Predictors

of Chiropractic Use Among US Adults Results

From the 2012 National Health Interview Survey

The data for this study was from the National Health Interview Survey, which is the principal and reliable source of comprehensive health care information in the United States.

The authors note that there are more than 70,000 practicing chiropractors in the United States. Chiropractors use manual therapy to treat musculoskeletal and neurological disorders. The authors state:

“Chiropractic is one of the largest manual therapy professions in the United States and internationally.”

“Chiropractic is one of the commonly used complementary health approaches in the United States and internationally.”

“There is a growing trend of chiropractic use among US adults from 2002 to 2012.”

“Back pain (63.0%) and neck pain (30.2%) were the most prevalent health problems for chiropractic consultations and the majority of users reported chiropractic helping a great deal with their health problem and improving overall health or well-being.”

“A substantial proportion of US adults utilized chiropractic services during the past 12 months and reported associated positive outcomes for overall well-being…”

“Our analyses show that, among the US adult population, spinal pain and problems – specifically for back pain and neck pain – have positive associations with the use of chiropractic.”

“The most common complaints encountered by a chiropractor are back pain and neck pain and is in line with systematic reviews identifying emerging evidence on the efficacy of chiropractic for back pain and neck pain.”

“Chiropractic services are an important component of the healthcare profession for patients affected by musculoskeletal disorders (especially for back pain and neck pain) and/or for maintaining their overall well-being.”

Many other clinical trials show that chiropractic care and spinal manipulation are safe and effective treatments for back pain (14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20). As a consequence, back pain clinical guidelines routinely advocate chiropractic care and spinal manipulation for the treatment of back pain (21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26).

•••••••••

Spinal joints bear weight. Weight-bearing joints commonly sustain wear-and-tear changes known as arthritis. The primary weight-bearing structure of the low back are the intervertebral disks (disk). Disk arthritic changes are often termed degenerative disk disease. Degenerative disk disease is often seen and diagnosed using spinal radiographs (x-rays).

Many healthcare providers, including many who specialize in the treatment of low back pain, attribute low back pain to spinal degenerative disk disease. However, such an association may be displaced. The incidence of low back pain is essentially the same in those with x-ray demonstrated degenerative disk disease as those who have no arthritic changes (27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32). This concept was profiled, in detail, by Nikolai Bogduk, MD, PhD, in an article published in the journal Radiological Clinics of North America, and titled (33):

Degenerative Joint Disease of the Spine

Nikolai Bogduk, MD, PhD, is an emeritus professor from the University of Newcastle, Australia. He has authored numerous books, chapters in books, and has 301 articles in PUBMED (as of November 2021).

Dr. Bogduk began research into spinal pain in 1972 when essentially nothing was known about the spinal pain. His anatomical studies have established the basis for causes of spinal pain. He has performed the anatomical studies and clinical trials to disprove many of the myths in pain-centered medical practice.

In this study, Dr. Bogduk notes that the most common reason that patients undergo spinal imaging is because of spinal pain. When this imaging shows degenerative disk disease, the provider assumes that the degeneration is the cause of the patient’s pain. Yet, Dr. Bogduk insists that it is not, noting there is NO clinically significant association between degenerative changes and low back pain.

Dr. Bogduk establishes that spinal degenerative disease is nothing more than a component of the normal aging process, similar in mechanism to grey hair and skin wrinkles. He states:

“Degenerative changes are normal age changes.”

“There is no known mechanism whereby degenerative changes can be painful, and the epidemiologic evidence shows that they are not.”

“Degenerative changes in the lumbar intervertebral disks or zygapophysial joints do not correlate with back pain.”

“Degenerative changes are not symptomatic.”

“Degenerative changes are irrelevant to spinal pain.”

“Degenerative changes have no correlation with neck pain, and no useful correlation with back pain.”

So, where is low back pain coming from? The evidence presented by Dr. Bogduk is that the most consistent site for low back pain is an intervertebral disk problem called internal disk disruption.

Internal disk disruption exists independently of spinal arthritic changes. Internal disk disruption is characterized by isolated radial fissures through the annulus fibrosus of lumbar intervertebral disks that do not breach the outer annulus. They are caused by injury to the vertebral end-plates (Modic changes). The vertebral end plates are susceptible to fatigue failure when subjected to repeated compression loads. The end-plate can also be injured from a sudden significant compression injury. The end-plate injury is the cause of the internal disk disruption.

Internal disk disruption is the most thoroughly studied, putative source of chronic back pain. Internal disk disruption is common. The “radial fissures are neither degenerative nor age changes.” The radial fissures “occur independently of age or degenerative changes.”

Internal disk disruption is NOT a representative of degenerative changes. Internal disk disruption DOES correlate with back pain.

Internal disk disruption cannot be seen or diagnosed on plain x-rays or with conventional CT scans. However, MRI scans often display a finding that is highly correlated with internal disk disruption: high-intensity zones. High-intensity zones are a bright white MR signal in the annulus of the disk and represent a fissure/tear; they represent circumferential tears in the annulus. Radial tears that enlarge can become circumferential tears.

The best diagnostic imaging to diagnose internal disk disruption is CT-diskography. However, there is evidence that diskography may harm the disk and accelerate disk degeneration (34).

The findings of Modic changes (end-plate fractures), high intensity zones, and a positive pain response to CT diskogram establish a definitive diagnosis of internal disk disruption.

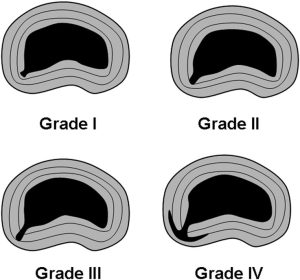

The fissures of internal disk disruption are graded according to the extent to which they penetrate the annulus:

Dr. Bogduk notes:

“Internal disk disruption is characterized by the presence of isolated, radial fissures penetrating from the nucleus pulposus into the annulus fibrosus but without breaching the outer annulus.”

“High-intensity zones and Modic changes correlate with the disk being painful.”

Radial fissures are “strongly associated with the affected disk being painful on diskography.”

“Internal disk disruption is common amongst patients with chronic back pain.”

The end-plate injury and the tears of the disk matrix generate abnormal disk stresses and accelerate disk degradation. Once the matrix is degraded, normal activities of daily living progressively tear elements of the annulus. Once the nuclear matrix is degraded, the ability of the nucleus to sustain compressive loads is compromised.

Abnormal disk stresses also generate an inflammatory chemical change that depolarizes disk nociceptors (noxious chemicals). Chemical nociception sensitize the nociceptors, rendering them more susceptible to mechanical nociception.

With advancing changes, crosslinking of collagen stiffens the disk matrix, “which can be detected biomechanically or expressed clinically as reduced range of movement.” This stiffness “opens” the pain gate, driving another mechanism for back pain (15, 35, 36).

Eventually the disk will depressurize, dehydrate, and then desiccate. The loss of fluid is reflected as reduced signal intensity on MR imaging.

The resulting spinal stiffness allows the disk to further accumulate inflammatory nociceptive chemicals while adding to more abnormal cross-linking of matrix collagen fibers. The positive feedback loop will not self resolve and interventional help is required.

Canadian orthopedic surgeon William H. Kirkaldy-Willis, MD, offers a solution (15). He presented a series of 283 chronic, disabled, treatment resistant low back pain patients who were referred to a practicing chiropractor for spinal manipulation. The outcomes were exceptional. Essentially 81% of the patients recovered, especially those who were not suffering from compressive neuropathology.

Dr. Kirkaldy-Willis explains his results by using Ronald Melzack’s and Patrick Wall’s 1965 Gate Theory of Pain (35, 36). He notes that this theory has “withstood rigorous scientific scrutiny.” He states:

“The central transmission of pain can be blocked by increased proprioceptive input.” Pain is facilitated by “lack of proprioceptive input.” This is why it is important for “early mobilization to control pain after musculoskeletal injury.”

“Increased proprioceptive input in the form of spinal mobility tends to decrease the central transmission of pain from adjacent spinal structures by closing the gate. Any therapy which induces motion into articular structures will help inhibit pain transmission by this means.”

Dr. Kirkaldy-Willis notes that in cases of chronic low back pain, there is a shortening of articular connective tissues and intra-articular adhesions may form. Spinal manipulations can stretch or break these adhesions, restoring mobility. This approach may also remodel the abnormal disk matrix cross linkages (37).

When Vert Mooney, MD, was the president of the International Society for the Study of the Lumbar Spine, his Presidential Address emphasized the following concepts (38):

Where Is the Pain Coming From?

Wound healing results in scar [fibrosis] formation which is less functional than the original tissue. Yet, early mobilization reduces scar and enhances recovery.

Degenerative spine disease, like grey hair and wrinkled skin, has an onward march of pathologic changes. The incidence of back pain peaks in the middle years and diminishes in the aged. Consequently, degenerative arthritis of the spine cannot be defined as the major cause of chronic back pain.

“The gradual symmetric aging process is not painful but the nonsymmetric disruptive process (perhaps with abnormal nutrition due to the asymmetry) is persistently painful.”

“Persistent pain in the back with referred pain to the leg is largely on the basis of abnormalities within the disk.”

“In the United States in the decade from 1971 to 1981, the numbers of those individuals disabled from low-back pain grew at a rate 14 times that of the population growth. This is a greater growth of medical disability than any other. Yet this growth occurred in the very decade when there was an explosion of ergonomic knowledge, labor-saving mechanical assistance devices, and improved diagnostic equipment. We apparently could not find the source of pain.”

“Six weeks to 2 months is usually enough to heal any stretched ligament, muscle tendon, or joint capsule. Yet we know that 10% of back ‘injuries’ do not resolve in 2 months and that they do become chronic.”

“Anatomically the motion segment of the back is made up of two synovial joints and a unique relatively avascular tissue found nowhere else in the body – the intervertebral disk. Is it possible for the disk to obey different rules of damage than the rest of the connective tissue of the musculoskeletal system?”

“Mechanical events can be translated into chemical events related to pain.”

“The fluid content of the disk can be changed by mechanical activity.”

“Mechanical activity has a great deal to do with the exchange of water and oxygen concentration” [in the disk].

An important aspect of disk nutrition and health is the mechanical aspects of the disk related to the fluid mechanics.

The pumping action maintains the nutrition and biomechanical function of the intervertebral disk.

“Research substantiates the view that unchanging posture, as a result of constant pressure such as standing, sitting or lying, leads to an interruption of pressure-dependent transfer of liquid. Actually, the human intervertebral disk lives because of movement.”

“In summary, what is the answer to the question of where is the pain coming from in the chronic low-back pain patient? I believe its source, ultimately, is in the disk. Basic studies and clinical experience suggest that mechanical therapy is the most rational approach to relief of this painful condition.”

“Prolonged rest and passive physical therapy modalities no longer have a place in the treatment of the chronic problem.”

Summary

Arthritic changes of the spine (disk and facet joints) are normal, essentially universal in the aged, and are non-painful.

In contrast, injury to the vertebral end-plates and internal disk disruption is not a part of the normal aging process, and they are the primary cause for chronic low back pain.

Internal disk disruption alters the disk matrix in such a way that inflammatory pain-producing chemicals accumulate. It is difficult for the disk to disperse these chemicals because the disk is avascular (has no blood supply). Chronic accumulation of inflammatory chemicals results in chronic low back pain.

Additionally, internal disk disruption will attempt to heal by producing abnormal cross-links of collagen proteins. This further impairs motion and the ability to disperse the accumulation of inflammatory chemicals. The reduced motion also opens the pain gate.

Chiropractic manipulation can remodel the disk matrix and thereby improve segmental motion. The improved motion closes the pain gate and activates a pumping mechanism (through the porous cartilaginous end-plates) that disperses the accumulated inflammatory chemicals. As stated by Dr. Vert Mooney above:

“Actually, the human intervertebral disk lives because of movement.”

The results are less pain and improved function.

REFERENCES

- Foreman J; A Nation in Pain, Healing Our Biggest Health Problem; Oxford University Press; 2014.

- Pho, K; USA TODAY, The Forum; September 19, 2011; pg. 9A.

- Wang S; Why Does Chronic Pain Hurt Some People More?; Wall Street Journal; October 7, 2013.

- Porter J, Jick H; New England Journal of Medicine; January 1980; Vol. 302; No. 2; p. 123.

- Portenoy RK, Foley KM; Chronic Use of Opioid Analgesics in Non-malignant Pain: Report of 38 cases; Pain; May 1986; 25; No. 5; pp. 171–186.

- Jones MR, Viswanath O, Peck J, Kaye AD, Gill JS, Simopoulos TT; A Brief History of the Opioid Epidemic and Strategies for Pain Medicine; Pain Therapy; June 2018; Vol. 7; No. 1; pp. 13-21.

- Krebs EE; Gravely A; Nugent S; Jensen AC; DeRonne B; Goldsmith ES; Kroenke K; Bair MJ; Noorbaloochi S; Effect of Opioid vs Non-opioid Medications on Pain-Related Function in Patients With Chronic Back Pain or Hip or Knee Osteoarthritis Pain: The SPACE Randomized Clinical Trial; Journal of the American Medical Association; March 6, 2018; Vol. 319; No. 9; pp. 872-882.

- Irving D; Opioid Rising: How to Stop the World’s Growing Heroin Crisis; October 20, 2015.

- Stobbe M; Overdose Deaths Hit Record Number Amid Pandemic; Associated Press; July 15, 2021.

- McKay B; U.S. Drug Overdose Deaths Soared Nearly 30%; Wall Street Journal; July 15, 2021.

- Wallis C; Painkiller Risks: Advil, Tylenol and the Like—Increasingly Used to Replace Opioids—Have Downsides; Scientific American; November 2021; p. 25.

- Abbasi J; Researching Nondrug Approaches to Pain Management; Medical News & Perspectives; An Interview with Robert Kerns, PhD; Journal of the American Medical Association; March 28, 2018; E1.

- Adams J, Peng W, Cramer H, Sundberg T, Moore C; The Prevalence, Patterns, and Predictors of Chiropractic Use Among US Adults; Results From the 2012 National Health Interview Survey; Spine; December 1, 2017; Vol. 42; No. 23; pp. 1810–1816.

- Kirkaldy-Willis WH; Managing Low Back Pain; Churchill Livingstone; 1983 and 1988.

- Kirkaldy-Willis WH, Cassidy JD; Spinal Manipulation in the Treatment of Low Back Pain; Canadian Family Physician; March 1985; Vol. 31; pp. 535-540.

- Meade TW, Dyer S, Browne W, Townsend J, Frank OA; Low back pain of mechanical origin: Randomized comparison of chiropractic and hospital outpatient treatment; British Medical Journal; Volume 300; June 2, 1990; pp. 1431-1437.

- Giles LGF, Muller R; Chronic Spinal Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial Comparing Medication, Acupuncture, and Spinal Manipulation; Spine; July 15, 2003; Vol. 28; No. 14; pp. 1490-1502.

- Muller R, Lynton G.F. Giles LGF, DC, PhD; Long-Term Follow-up of a Randomized Clinical Trial Assessing the Efficacy of Medication, Acupuncture, and Spinal Manipulation for Chronic Mechanical Spinal Pain Syndromes; Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics; January 2005; Vol. 28; No. 1; pp. 3-11.

- Cifuentes M, Willetts J, Wasiak R; Health Maintenance Care in Work-Related Low Back Pain and Its Association With Disability Recurrence; Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine; April 14, 2011; Vol. 53; No. 4; pp. 396-404.

- Senna MK, Machaly SA; Does Maintained Spinal Manipulation Therapy for Chronic Nonspecific Low Back Pain Result in Better Long-Term Outcome? Randomized Trial; Spine; August 15, 2011; Vol. 36; No. 18; pp. 1427–1437.

- Chou R, Qaseem A, Snow V, Casey D, Cross JT, Shekell, Owens DK; Diagnosis and Treatment of Low Back Pain; Annals of Internal Medicine; Vol. 147; No. 7; October 2007; pp. 478-491.

- Chou R, Huffman LH; Non-pharmacologic Therapies for Acute and Chronic Low Back Pain; Annals of Internal Medicine; October 2007; Vol. 147; No. 7; pp. 492-504.

- Globe G, Farabaugh RJ, Hawk C, Morris CE, Baker G, DC, Whalen WM, Walters S, Kaeser M, Dehen M, DC, Augat T; Clinical Practice Guideline: Chiropractic Care for Low Back Pain; Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics; January 2016; Vol. 39; No. 1; pp. 1-22.

- Wong JJ, Cote P, Sutton DA, Randhawa K, Yu H, Varatharajan S, Goldgrub R, Nordin M, Gross DP, Shearer HM, Carroll LJ, Stern PJ, Ameis A, Southerst D, Mior S, Stupar M, Varatharajan T, Taylor-Vaisey A; Clinical practice guidelines for the noninvasive management of low back pain: A systematic review by the Ontario Protocol for Traffic Injury Management (OPTIMa) Collaboration; European Journal of Pain; Vol. 21; No. 2; February 2017; pp. 201-216.

- Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, Forciea MA; Noninvasive Treatments for Acute, Subacute, and Chronic Low Back Pain: A Clinical Practice Guideline from the American College of Physicians; For the Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians; Annals of Internal Medicine; April 4, 2017; Vol. 166; No. 7; pp. 514-530.

- Oliveira CB, Maher CG, Pinto RZ, et al.; Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Non-Specific Low Back Pain in Primary Care: An Updated Overview; European Spine Journal; November 2018; Vol. 27; No. 11; pp. 2791-2803.

- Boden SD, Davis DO, Dina TS, Patronas NJ, Wiesel SW; Abnormal magnetic-resonance scans of the lumbar spine in asymptomatic subjects. A prospective investigation; Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery; March 1990; Vol. 72; No. 3; pp. 403-408.

- Greenberg JO, Schnell; Magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine in asymptomatic adults. Cooperative study–American Society of Neuroimaging; Journal of Neuroimaging; February 1991; Vol. 1; No. 1; pp. 2-7.

- Jensen MC, Brant-Zawadzki MN, Obuchowski N, Modic MT, Malkasian G, Ross JS; Magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine in people without back pain; New England Journal of Medicine; July 14, 1994; Vol. 331; Vol. 2; pp. 69-67.

- Kanayama M, Togawa D, Takahashi C, Terai T, Hashimoto T; Cross-sectional magnetic resonance imaging study of lumbar disc degeneration in 200 healthy individuals; Journal of Neurosurgery Spine; October 2009; Vol. 11; No. 4; pp. 501-507.

- Kalichman L, Kim DH, Li L, Guermazi A, Hunter DJ; Computed tomography-evaluated features of spinal degeneration: prevalence, intercorrelation, and association with self-reported low back pain; Spine Journal; March 2010; Vol. 10; No. 3; pp. 200-208.

- Brinjikji W, Luetmer PH, Comstock B, Bresnahan BW, Chen LE, Deyo RA, Halabi S, Turner JA, Avins AL, James K, Wald JT, Kallmes DF, Jarvik JG; Systematic Literature Review of Imaging Features of Spinal Degeneration in Asymptomatic Populations; American Journal of Neuroradiology (AJNR); April 2015; Vol. 36; No. 4; pp. 811–816.

- Bogduk N; Degenerative Joint Disease of the Spine; Radiological Clinics of North America; July 2012; Vol. 50; No. 4; pp. 613-628.

- Carragee EJ, Don AS, Hurwitz EL, Cuellar JM, Carrino J, Herzog R; Does Discography Cause Accelerated Progression of Degeneration Changes in the Lumbar Disc: A Ten-Year Matched Cohort Study; Spine; October 1, 2009; Vol. 34; No. 21; pp. 2338–2345.

- Melzack R, Wall P; Pain Mechanisms: A New Theory; Science; November 19, 1965; Vol. 150; No. 3699; pp. 971-979.

- Dickenson AH; Gate Control Theory of Pain Stands the Test of Time; British Journal of Anaesthesia; June 2002; Vol. 88; No. 6; pp. 755-757.

- Cyriax J; Textbook of Orthopaedic Medicine, Diagnosis of Soft Tissue Lesions; Bailliere Tindall; Vol. 1; Eighth edition; 1982.

- Mooney V; Where Is the Pain Coming From?; Spine; October 1987; Vol. 12; No. 8; pp. 754-759.

“Authored by Dan Murphy, D.C.. Published by ChiroTrust® – This publication is not meant to offer treatment advice or protocols. Cited material is not necessarily the opinion of the author or publisher.”