Upper Cervical Spine Chiropractic Care

The Vagus Nerve and Musculoskeletal Pain

By a wide margin, people go to chiropractors for the management of musculoskeletal pain. Recent formal reviews of the chiropractic profession indicate that 93% of chiropractic patients initially seek chiropractic care for spinal pain complaints: 63% for low back pain and 30% for neck pain. Patient satisfaction with their chiropractic care is exceptionally high (1).

A central tenant to the understanding of pain is that pain is linked to inflammation. This was nicely reviewed in the journal Medical Hypothesis in 2007 in an article titled (2):

The Biochemical Origin of Pain:

The Origin of All Pain is Inflammation

and the Inflammatory Response

The author, Sota Omoigui, MD, the medical director of the Los Angeles Pain Clinic, states:

“Every pain syndrome has an inflammatory profile consisting of the inflammatory mediators that are present in the pain syndrome.”

“The key to treatment of Pain Syndromes is an understanding of their inflammatory profile.”

“Our unifying theory or law of pain states: the origin of all pain is inflammation and the inflammatory response.”

“Irrespective of the type of pain whether it is acute or chronic pain, peripheral or central pain, nociceptive or neuropathic pain, the underlying origin is inflammation and the inflammatory response.”

“Activation of pain receptors, transmission and modulation of pain signals, neuro-plasticity and central sensitization are all one continuum of inflammation and the inflammatory response.”

“Irrespective of the characteristic of the pain, whether it is sharp, dull, aching, burning, stabbing, numbing or tingling, all pain arises from inflammation and the inflammatory response.”

The most common treatment of inflammatory pain is consumption of drugs, specifically non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). However, when these drugs (NSAIDs) are taken for chronic pain, there are many serious side effects. In 2003, the journal Spine stated (3):

“Adverse reactions to non-steroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAID) medication have been well documented.”

“Gastrointestinal toxicity induced by NSAIDs is one of the most common serious adverse drug events in the industrialized world.”

“The newer COX-2-selective NSAIDs are less than perfect, so it is imperative that contraindications be respected.”

“[There is] insufficient evidence for the use of NSAIDs to manage chronic low back pain, although they may be somewhat effective for short-term symptomatic relief.”

In 2006, the journal Surgical Neurology states (4):

Blockage of the COX enzyme inhibits the conversion of arachidonic acid to the very pro-inflammatory prostaglandins that mediate the classic inflammatory response of pain.

“More than 70 million NSAID prescriptions are written each year, and 30 billion over-the-counter NSAID tablets are sold annually.”

“5% to 10% of the adult US population and approximately 14% of the elderly routinely use NSAIDs for pain control.”

Almost all patients who take the long-term NSAIDs will have gastric hemorrhage, 50% will have dyspepsia, 8% to 20% will have gastric ulceration, 3% of patients develop serious gastrointestinal side effects, which results in more than 100,000 hospitalizations, an estimated 16,500 deaths, and an annual cost to treat the complications that exceeds 1.5 billion dollars.

“NSAIDs are the most common cause of drug-related morbidity and mortality reported to the FDA and other regulatory agencies around the world.”

One author referred to the “chronic systemic use of NSAIDs to ‘carpet-bombing,’ with attendant collateral end-stage damage to human organs.”

In May 2022, an article was published pertaining to the use of anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs or steroids) and the future incidence of chronic low back pain. It was published in the journal Science Translational Medicine, titled (5):

Acute Inflammatory Response Via Neutrophil Activation

Protects Against the Development of Chronic Pain

The authors note that treating the inflammation and pain of low back pain (LBP) with NSAIDs or steroid drugs would significantly increase the risk of suffering from chronic low back pain. The authors state:

“Early treatment with a steroid or nonsteroidal anti- inflammatory drug (NSAID) led to prolonged pain despite being analgesic in the short term.”

“Drugs that inhibit inflammation might interfere with the natural recovery process, thus increasing the odds for chronic pain.”

“Results indicate the importance of the up-regulation of the inflammatory response at the acute stage of musculoskeletal pain as a protective mechanism against the development of chronic pain.”

The acute treatment of inflammation with either a steroid or a NSAID, “although both effectively reducing pain behavior during their administration—greatly prolonged the resolution of neuropathic, myofascial, and especially inflammatory pain states.”

“Individuals with acute back pain were at greater risk [76%] of developing chronic back pain if they reported NSAID usage than if they were not taking NSAIDs, adjusting for age, sex, [and] ethnicity.”

The use of anti-inflammatory drugs for pain management has many concerns. These drugs are not very effective. They are associated with multiple serious side-effects in a linear fashion (the more one takes, the greater the risks of suffering side-effects). These drugs for acute back pain may significantly increase the risk of becoming a chronic back pain sufferer.

Traditional Chiropractic Care

Chiropractic care is known for using joint adjusting (specific line-of-drive manipulation) for the management of spine pain syndromes. Chiropractors are also legally allowed to use a variety of non-drug based anti-inflammatory modalities, like an ice pack.

However, one should ask: If treating the inflammation and pain of low back pain was as simple as using an ice pack, why would society need a chiropractor?

It has been known for decades that chronic low back pain arises primarily from the intervertebral disc (IVD) (6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12). Anatomically, the IVD is located deep within the human body. When viewing the human body from the side, in a normal weight person, the IVD is located near the center of the lumbar spine (low back).

The depth of the location of the IVD makes it improbable for a topical application of ice to be very effective. Yet, a different therapeutic model and approach to the management of chronic LBP is offered by Vert Mooney, MD (8).

Dr. Vert Mooney, MD, was a renowned and respected orthopedic surgeon. He was trained at Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons (medical school) and at the University of Pittsburgh (Orthopedic Surgery Resudency). He died in 2009.

Dr. Mooney was a founding member of the North American Spine Society (NASS), and he served as NASS President from 1987-1988. He also received the Lifetime Achievement Award in Lumbar Spine Research from the International Society for the Study of the Lumbar Spine in 2008. His area of specialty was advocating for non-surgical approaches to the management of acute and chronic lumbo-pelvic pain and the promotion of interdisciplinary approaches to the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of lower back spinal problems.

In his 1986 Presidential Address to the International Society for the Study of the Lumbar Spine, Dr. Mooney made these comments, published in the journal Spine, in an article titled (8):

Where Is the Pain Coming From?

“In the United States in the decade from 1971 to 1981, the numbers of those individuals disabled from low-back pain grew at a rate 14 times that of the population growth. This is a greater growth of medical disability than any other. Yet this growth occurred in the very decade when there was an explosion of ergonomic knowledge, labor-saving mechanical assistance devices, and improved diagnostic equipment. We apparently could not find the source of pain.”

“Anatomically the motion segment of the back is made up of two synovial joints and a unique relatively avascular tissue found nowhere else in the body – the intervertebral disc. Is it possible for the disc to obey different rules of damage than the rest of the connective tissue of the musculoskeletal system?”

“Mechanical events can be translated into chemical events related to pain.”

“Mechanical activity has a great deal to do with the exchange of water and oxygen concentration” in the disc.

An important aspect of disc nutrition and health is the mechanical aspects of the disc related to the fluid mechanics.

The pumping action maintains the nutrition and biomechanical function of the intervertebral disc. Thus, “research substantiates the view that unchanging posture, as a result of constant pressure such as standing, sitting or lying, leads to an interruption of pressure-dependent transfer of liquid. Actually, the human intervertebral disc lives because of movement.”

“The fluid content of the disc can be changed by mechanical activity.”

“In summary, what is the answer to the question of where is the pain coming from in the chronic low-back pain patient? I believe its source, ultimately, is in the disc. Basic studies and clinical experience suggest that mechanical therapy is the most rational approach to relief of this painful condition.”

This model and approach to the management of low back pain has supported the chiropractic perspective for decades:

- The intervertebral disc (IVD) is the primary source of chronic low back pain.

- Like any other tissue in the body, the IVD will accumulate meaningful (pain producing) amounts of inflammatory chemicals. This will occur as a consequence of injury, chronic stress, excessive weight, age, etc. Reducing these inflammatory chemicals with drugs is very problematic: they do not work very well, they are coupled with many side effects (some are very serious including death (13)), and they increase the risk of chronicity.

- The disc is anatomically unique: it does not have a blood supply. This anatomical fact explains why chronic discogenic low back pain is not much improved with anti-inflammatory drugs. The chemicals cannot penetrate effectively into the disc because of the lack of blood supply.

- As nicely explained above by Dr. Mooney, the only way to disperse the inflammatory chemicals of chronic back pain is through motion. Above and below the avascular IVD are very porous cartilaginous end- Motion literally pumps the inflammatory chemicals through the porous cartilaginous end-plates into the very vascular vertebral bodies, dispersing their accumulation.

- Chronic back pain patients have reduced segmental mobility. Chiropractors have the unique ability to locate the level and direction of this lack of mobility and to improve it with the delivery of the spinal adjustment. The chiropractic approach is exceptionally effective and accomplished without adverse events (15). Chiropractic care for back pain is highly effective, has high levels of patient satisfaction, routinely out performs pain drugs in randomized clinical trials, and carries none of the risks associated with pain drugs.

The Vagus Nerve and Systemic Inflammation

A method of categorizing the peripheral nervous system is by distinguishing between cranial nerves and spinal nerves. Spinal nerves exit between the spinal column vertebrae. Cranial nerves exit from the skull. For the most part, cranial nerves originate in the brain or brainstem. There is one exception to this, but it is irrelevant to this discussion. The most important cranial nerve is the vagus nerve, also known as cranial nerve X (ten).

The word “vagus,” from Latin, means “wandering.” The vagus nerve is so named because it meanders throughout the neck, chest, and abdomen, innervating most of the viscera. As we will discuss, this includes the viscera responsible for controlling one’s systemic inflammatory profile.

The vagus nerve is both a motor (output, efferent) and a sensory (input, afferent) nerve. Of the 160,000 fibers in the vagus nerve, 80% are sensory and 20% are motor.

The August 26, 2023 issue of the journal New Scientist featured the relevance and importance of the vagus nerve (16). The article asks:

“What diseases are affected by inflammation?

Pretty much every chronic illness.”

The article then details how the vagus nerve mediates systemic inflammation. This includes the inflammation associated with chronic musculoskeletal syndromes.

In 2019, an article was published in the journal Frontiers in Neuroscience (17). The authors are truly an international group, located in Austria, Germany, Spain, Italy, Belgium, Switzerland, Lithuania, and Poland. This article profiles the ability of the vagus nerve to modulate nociceptive (pain) processing. The authors note that the antinociceptive effects of vagus nerve stimulation have been shown in numerous clinical trials.

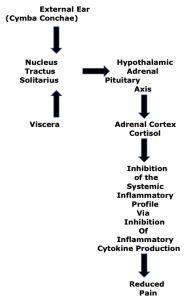

Their explanation for the value of vagus nerve optimization is that the body’s response to infection and/or injury is the same. Both initially activate the innate immune system’s key player, the macrophage. Macrophages “clean-up” the area of infection or injury by producing pro-inflammatory proteins called cytokines. After the initial “clean-up” is completed, the production of these inflammatory cytokines must be halted, and the vagus nerve coordinates this shutdown with a systemic anti-inflammatory cascade through the adrenal gland. This is depicted in a graph below.

In 2021, researchers from Sorbonne University and Saint-Antoine Hospital, both in Paris, France, published an article in the journal Joint Bone Spine, titled (18):

Vagus Nerve Stimulation in Musculoskeletal Diseases

In this article, the authors also emphasize the anti-inflammatory and analgesic functions of the vagus nerve. They specifically review studies pertaining to the pain of arthritis, fibromyalgia, migraine headache, and inflammatory bowel disease. They also use the macrophage-cytokine-adrenal systemic inflammatory model, as noted below:

The Nucleus Tractus Solitarius is the sensory nucleus of the vagus nerve, located in the medulla.

Upper Cervical Chiropractic Care

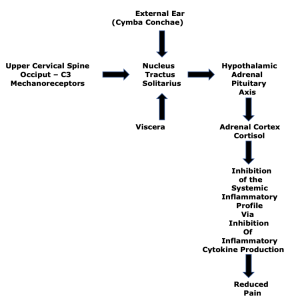

Chiropractic education holds that the mechanoreceptors of the upper cervical spine, occiput through C3, influence the vagus nerve. Hence, upper cervical chiropractic adjustments and postural improvements will activate vagus nerve driven reduction of the systemic inflammatory profile, reducing pain throughout the body. This pathway is added to the above graphic, below:

This perspective was significantly advanced in 2007 when a study was published in the Journal of Neuroscience, titled (19):

The Neurochemically Diverse Intermedius Nucleus

of the Medulla as a Source of Excitatory and

Inhibitory Synaptic Input to the Nucleus Tractus Solitarii

The authors are biologists from the University of Leeds in the United Kingdom. Thy explain these points:

- The autonomic nervous system has two branches: the sympathetic nervous system and the parasympathetic nervous system.

- The nucleus tractus solitarius of the medulla is the principal sensory nucleus of the vagus

- The vagus nerve is the primary contributor to the parasympathetic nervous system.

- The parasympathetic nervous system must be in balance with the sympathetic nervous system. Increasing parasympathetic tone will decrease sympathetic tone, and vice versa. Increased parasympathetic tone is anti-inflammatory. Increased sympathetic tone is inflammatory.

- Upper cervical mechanoreceptors input to the sensory nucleus of the vagus nerve (nucleus tractus solitarius), increasing parasympathetic tone and decreasing sympathetic

These authors state:

“[There are] interactions between the somatic and autonomic nervous systems.”

“[Somatic] sensory afferent input to the spinal cord, is then relayed to the nucleus tractus solitarius (NTS).”

These spinal somatic reflex circuits include the tonic neck reflexes involved in postural control.

“[The nucleus tractus solitarius] has been shown to receive afferent inputs from neck muscles.”

“Additional evidence for the involvement of the suboccipital muscle group in the cervico-sympathetic reflex comes from changes in blood pressure associated with chiropractic manipulations of the C1 vertebrae, which would result in altering the length of fibers in the suboccipital muscle group.”

These concepts were further supported in 2009 when this same group published a study in the Journal of Chemical Neuroanatomy, titled (20):

The Intermedius Nucleus of the Medulla:

A Potential Site for the Integration of Cervical Information

and the Generation of Autonomic Responses

In this publication, the authors add:

“[The nucleus tractus solitarius is] heavily influenced by the position of the head relative to the trunk.”

“Changes in the positioning of the head relative to the trunk, or sensory information arising from the neck musculature, have been clinically implicated in the control of [vagus nerve activity].”

“[This pathway from the neck musculature to the vagus nerve might be behind the] changes in heart rate and blood pressure observed following upper cervical chiropractic manipulations and autonomic disturbances observed in whiplash patients.”

Lastly, in 2015, these authors add more support for these concepts with a publication in the journal Brain Structure & Function, in an article titled (21):

Neck Muscle Afferents Influence Oromotor

and Cardiorespiratory Brainstem Neural Circuits

In this article, the authors add to the details of how the mechanoreceptors and proprioceptors of the upper cervical spine influence the vagus nerve.

In summary, proprioceptive information from the joints and muscles of the upper cervical spine play an important role in modulating the vagus nerve and one’s systemic inflammatory profile. This can suppress pain at any location in the body. These studies add to the support of upper cervical spine chiropractic care for musculoskeletal pain syndromes.

REFERENCES

- Adams J, Peng W, Cramer H, Sundberg T, Moore C; The Prevalence, Patterns, and Predictors of Chiropractic Use Among US Adults; Results From the 2012 National Health Interview Survey; Spine; December 1, 2017; Vol. 42; No. 23; pp. 1810–1816.

- Omoigui S; The Biochemical Origin of Pain: The Origin of All Pain is Inflammation and the Inflammatory Response: Inflammatory Profile of Pain Syndromes; Medical Hypothesis; 2007; Vol. 69; No. 6; pp. 1169–1178.

- Giles LGF, Muller R; Chronic Spinal Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial Comparing Medication, Acupuncture, and Spinal Manipulation; Spine; July 15, 2003; Vol. 28; No. 14; pp. 1490-1502.

- Maroon JC, Bost JW; Omega-3 Fatty acids (fish oil) as an anti-inflammatory: An alternative to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for discogenic pain; Surgical Neurology; April 2006; Vol. 65; No. 4; pp. 326–331.

- Parisien M, Lima LV, Dagostino C, El-Hachem N, and 16 more; Acute Inflammatory Response Via Neutrophil Activation Protects Against the Development of Chronic Pain; Science Translational Medicine; May 11, 2022; Vol. 14; Article eabj9954.

- Nachemson AL; The Lumbar Spine, an Orthopedic Challenge; Spine; March 1976; Vol. 1; No. 1; pp. 59-71.

- Bogduk N, Tynan W, Wilson AS; The nerve supply to the human lumbar intervertebral discs; Journal of Anatomy; 1981; Vol. 132; No. 1; pp. 39-56.

- Mooney V; Where Is the Pain Coming From?; Spine; Vol. 12; No. 8; 1987; pp. 754-759.

- Kuslich S, Ulstrom C, Michael C; The Tissue Origin of Low Back Pain and Sciatica: A Report of Pain Response to Tissue Stimulation During Operations on the Lumbar Spine Using Local Anesthesia; Orthopedic Clinics of North America; April 1991; Vol. 22; No. 2; pp. 181-187.

- Ozawa T, Ohtori S, Inoue G, Aoki Y, Moriya H, Takahashi; The Degenerated Lumbar Intervertebral Disc is Innervated Primarily by Peptide-Containing Sensory Nerve Fibers in Humans; Spine; October 1, 2006; Vol. 31; No 21; pp. 2418-2422.

- DePalma MJ, Ketchum JM, Saullo T; What is the source of chronic low back pain and does age play a role?; Pain Medicine; February 2011; Vol. 12; No. 2; pp. 224-233.

- Izzo R, Popolizio T, D’Aprile P, Muto M; Spine Pain; European Journal of Radiology; May 2015; Vol. 84; No. 5; pp. 746–756.

- Wolfe MM, Lichtenstein DR, Singh G; Gastrointestional Toxicity of Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs; New England Journal of Medicine; June 17, 1999; Vol. 340; No. 24; pp. 1888-1899.

- Kapandji IA; The Physiology of the Joints; Volume 3; The Trunk and the Vertebral Column; Churchill Livingstone; 1974.

- Kirkaldy-Willis WH, Cassidy JD; Spinal Manipulation in the Treatment of Low back Pain; Canadian Family Physician; March 1985; Vol. 31; pp. 535-540.

- Wade G; Your Body’s Secret Superhighway: The Vagus Nerve Influences Everything from Your Heartbeat to Your Immune System; New Scientist; August 26, 2023; pp. 40-43.

- Kaniusas E, Kampusch S, Tittgemeyer M, Panetsos F, Gines RF, Papa M, Kiss A, Podesser B, Cassara AM, Tanghe E, Samoudi AM, Tarnaud T, Joseph W, Marozas V, Lukosevicius A, Ištuk N, Šaroli? A, Lechner S, Klonowski W, Varoneckas G, Széles JC; Current Directions in the Auricular Vagus Nerve Stimulation I: A Physiological Perspective; Frontiers in Neuroscience; August 9, 2019; Vol. 13; article 854.

- Courties A, Berenbaum F, Sellam J; Vagus Nerve Stimulation in Musculoskeletal Diseases; Joint Bone Spine; May 2021; Vol. 88; No. 3; article 105149.

- Edwards IJ, Dallas ML, Poole SL, Milligan CJ, Yanagawa Y, Szabo G, Erdelyi F, Deuchars SA, Deuchars J; The Neurochemically Diverse Intermedius Nucleus of the Medulla as a Source of Excitatory and Inhibitory Synaptic Input to the Nucleus Tractus Solitarii; Journal of Neuroscience; August 1, 2007; Vol. 27; No. 31; pp. 8324-8333.

- Edwards IJ, Deuchars SA, Deuchars J; The Intermedius Nucleus of the Medulla: A Potential Site for the Integration of Cervical Information and the Generation of Autonomic Responses; Journal of Chemical Neuroanatomy; November 2009; Vol 38; No. 3; pp. 166-175.

- Edwards IJ, Lall VK, Paton JF, Yanagawa Y, Szabo G, Deuchars SA, Deuchars J; Neck Muscle Afferents Influence Oromotor and Cardiorespiratory Brainstem Neural Circuits; Brain Structure and Function; 2015; Vol. 220; No. 3; pp. 1421-1436.

“Authored by Dan Murphy, D.C.. Published by ChiroTrust® – This publication is not meant to offer treatment advice or protocols. Cited material is not necessarily the opinion of the author or publisher.”