The Chiropractic Management of Discogenic Compressive Radicular Sciatica

The low back is the most common body region to suffer from chronic pain (1).

Low back pain is the second most common reason for primary care physician visits, and it is the most costly medical condition in the United States (2).

The most common tissue source for low back pain is the intervertebral disc (3, 4, 5, 6).

The primary clinical syndrome treated by chiropractors is chronic low back pain (7).

Chiropractic care is proven to be very successful in the treatment of chronic low back pain. Often, chiropractic care is superior to alternative types of management for chronic low back pain, including prescription nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, physical therapy, exercise, and needle acupuncture (8, 9, 10, 11, 12).

Long-term follow-up studies on these chronic patients show that chiropractic care obtains stable therapeutic benefits (9, 10, 12).

Chiropractic care is not only very effective for low back pain, it is also very safe. In some randomized clinical trials, not a single adverse event is reported of the study subjects randomized to receiving chiropractic spinal manipulation (10).

Definitions/Terminology

Radiculitis and Radiculopathy

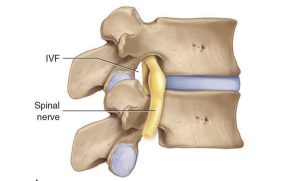

Between each and every spinal segmental level, a spinal nerve exits from the intervertebral foramen (IVF). The technical terminology for the spinal nerve is the nerve root. Spinal nerve root problems (compression, irritation, inflammation, pathology) are called radiculitis and/or radiculopathy. Radiculitis and Radiculopathy mean it is a nerve root problem.

Neuritis and Neuropathy

A peripheral nerve is made up of more than one nerve root. The technical terminology for a peripheral nerve uses the base neuro. Peripheral nerve problems (compression, irritation, inflammation, pathology) are called neuritis and/or neuropathy. Neuritis and Neuropathy mean it is a peripheral nerve problem.

Interim Discussion

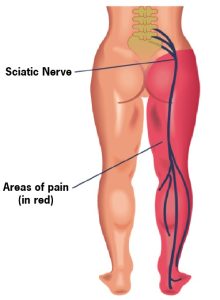

The sciatic nerve is a nerve that begins in the lower back and travels through the buttock and down into the back of the leg and then into the foot. It is the longest and widest nerve in the human body. The sciatic nerve is made up of five lumbosacral nerve roots, L4, L5, S1, S2, and S3.

When a nerve is compressed, irritated, or inflamed, it generates symptoms (pain, numbness, tingling, hypersensitivity, burning, achiness, etc.) and/or functional disturbances (weakness, atrophy, etc.).

The sciatic nerve is a peripheral nerve. When a peripheral nerve causes symptoms and/or signs, it is neuritis or neuropathy. Signs and symptoms attributed to the sciatic nerve are called sciatic neuritis or sciatic neuropathy. However, most people and most health care providers simply refer to it as sciatica.

If any of the nerve roots that make up the sciatic nerve are compressed, irritated, and/or inflamed, it will generate the signs and/or symptoms of sciatica. In such a circumstance, the technical terminology would be sciatic radiculitis or sciatic radiculopathy.

Leg Pain, Sciatica

Some patients with low back pain also suffer from leg pain. When leg pain is present, it often indicates that the pathoanatomical basis for the patient’s symptoms are more complex and that the resolution of the symptoms and signs will also be more complicated.

Clinicians usually view leg pain in three categories:

Category 1:

Sclerogenic pain; also known as Sclerotomic pain or Sclerotogenous pain

Sclerogenic leg pain occurs as a consequence of an irritation of low back tissues below the deep fascia (deep spinal muscles, facet capsule ligaments, annulus of the intervertebral disc, etc.). It often subjectively presents as a deep dull ache. It is rare for the discomfort to extend below the knee. It is difficult for the patient to precisely locate the pain on the skin; the discomfort is perceived deep to the skin. Lumbar spine vertical compression tests (including Kemp’s) are usually negative. Straight leg raising tests are usually negative. Superficial sensation is usually negative. Myotomal strength tests are usually normal. Deep tendon reflexes are usually normal and symmetrical.

In general, sclerogenic pain is not dangerous. It is a form of referred pain that occurs as a consequence of a shared neuromere during embryonic development. The neurology of the back and the leg are shared embryologically, which can cause some confusion as to the exact location of the irritation when the electrical signal is sent to the brain: an irritation of low back tissues might be interpreted by the brain as arising from the leg.

The original descriptions of sclerogenic pain were from the research of JH Kellgren and colleague in 1938 and 1939 (13, 14).

Chiropractic spinal adjustments (specific line-of-drive manipulations) primarily affect the deep spinal tissues (deep spinal muscles, facet capsule ligaments, annulus of the intervertebral disc, etc.). These are the same tissues that are responsible for the sclerogenic pain referral. Consequently, chiropractic spinal adjusting is very effective in improving and/or resolving both back pain and referred sclerogenic leg pain.

Category 2:

Peripheral Neuropathy

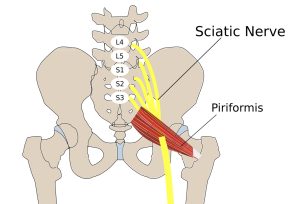

A peripheral neuropathy is NOT a nerve root problem. It is a compressed, irritated, and/or inflamed peripheral nerve. An example of a peripheral neuropathy is piriformis syndrome sciatica.

A recent review on piriformis syndrome sciatica reminds the reader that the sciatic nerve runs adjacent to the piriformis muscle and may even pierce through the muscle. The authors state (15):

“Piriformis syndrome is a clinical condition of sciatic nerve entrapment at the level of the ischial tuberosity.”

“Patients often report pain in the gluteal/buttock region that may ‘shoot,’ burn or ache down the back of the leg (i.e. ‘sciatic’-like pain).”

“Numbness in the buttocks and tingling sensations along the distribution of the sciatic nerve is not uncommon.”

When a peripheral neuropathy exists independent from radicular involvement, the treatment is to the peripheral lesion. In the example of piriformis syndrome sciatica, treatment would be to the piriformis muscle and to the hip joint. Pelvic unleveling could also be involved, requiring chiropractic evaluation and management.

Category 3:

Radicular Pain, Radiculitis, Radiculopathy

Radicular leg pain is often caused by compression of the nerve root, the compression causing nerve root irritation, inflammation, and/or ischemia. This pathology is referred to as compressive radiculopathy.

The most classic cause of radicular compression is herniation of the intervertebral disc. Other causes include arthritic changes (degenerative joint disease, degenerative disc disease, spondylosis) causing osseous (bone spurs, hypertrophic changes, osteophytes) narrowing of the intervertebral foramen.

The chiropractic (low back spinal manipulation) management of discogenic compressive radicular sciatica has a long history that includes publications in a range of medical journals and reference texts. A representative number of these studies are reviewed here.

•••••••••

In 1954, a study was published, titled (16):

Conservative Treatment of Intervertebral Disk Lesions

The author states:

“The conservative management of lumbar disk lesions should be given careful consideration because no patient should be considered for surgical treatment without first having failed to respond to an adequate program of conservative treatment.”

“If after a fair trial of conservative treatment, the pain and disability continue and the symptoms are of sufficient gravity to warrant surgery, the patient is advised that he should be operated upon and the offending disk lesion should be removed.”

“From what is known about the pathology of lumbar disk lesions, it would seem that the ideal form of conservative treatment would theoretically be a manipulative closed reduction of the displaced disk material.”

“We limit the use of manipulation almost entirely to those patients who do not seem to be responding well to non-manipulative conservative treatment and who are anxious to have something else done short of operative intervention.”

••••••••

In 1969, a study was published, titled (17):

Reduction of Lumbar Disc Prolapse by Manipulation

The authors evaluated patients that presented with an acute onset of low back and buttock pain that did not respond to rest. Diagnostic epidurography showed a clinically relevant disc herniation, along with antalgia and positive lumbar spine nerve stretch tests. These patients were then treated with lumbar spine rotation thrust manipulations. Manipulations were repeated until abnormal symptoms and signs had disappeared. Following the manipulations there was resolution of signs, symptoms, antalgia, and reduction in the size of the protrusions. The authors state:

“The frequent accompaniment of acute onset low back pain by spinal deformity suggests a mechanical factor, and the accompanying abnormality of straight-leg raise or femoral stretch test suggests that the lesion impinges on the spinal dura matter of the dural nerve sheaths.”

“The lumbar spine was rotated away from the painful side to the limit of its range, the buttock or thigh of the painful side being used as a lever; a firm additional thrust was made in the same direction. This manoeuver was repeated until abnormal symptoms and signs had disappeared, progress being assessed by repeated examination.”

“Rotation manipulations apply torsion stress throughout the lumbar spine. If the posterior longitudinal ligament and the annulus fibrosus are intact, some of this torsion force would tend to exert a centripetal force, reducing prolapsed or bulging disc material.”

“The results of this study suggest that small disc protrusions were present in patients presenting with lumbago and that the protrusions were diminished in size when their symptoms had been relieved by manipulations.”

These authors conclude: “it seems likely that the reduction effect [of the disc protrusion] is due to the manipulating thrust used.”

•••••••••

Also in 1969, a study was published, titled (18):

Low Back Pain and Pain Resulting from Lumbar Spine Conditions:

A Comparison of Treatment Results

The authors compared the effectiveness of heat/massage/exercise to spinal manipulation in the treatment of 184 patients that were grouped according to the presentation of back and leg pain. This study was then reviewed in their 1990 book, Clinical Biomechanics of the Spine, which made these points (19):

“A well-designed, well executed, and well-analyzed study.”

In the group with central low back pain only, “the results were acceptable in 83% for both treatments. However, they were achieved with spinal manipulation using about one-half the number of treatments that were needed for heat, massage, and exercise.”

In the group with pain radiating into the buttock, “the results were slightly better with manipulation, and again they were achieved with about half as many treatments.”

In the groups with pain radiation to the knee and/or to the foot, “the manipulation therapy was statistically significantly better,” and in the group with pain radiating to the foot, “the manipulative therapy is significantly better.”

“This study certainly supports the efficacy of spinal manipulative therapy in comparison with heat, massage, and exercise. The results (80–95% satisfactory) are impressive in comparison with any form of therapy.”

•••••••••

In 1977, the third edition of the text book Orthopaedics, Principles and Their Applications was published. The author made these observations (20):

Treatment of Intervertebral Disc Herniation With Manipulation

“Manipulation. Some orthopaedic surgeons practice manipulation in an effort at repositioning the disc. This treatment is regarded as controversial and a form of quackery by many men. However, the author has attempted the maneuver in patients who did not respond to bed rest and were regarded as candidates for surgery. Occasionally, the results were dramatic.”

•••••••••

In 1987, a study was published, titled (21):

Treatment of Lumbar Intervertebral Disc Protrusions by Manipulation

The authors performed a series of eight manipulations on 517 patients with protruded lumbar discs and clinically relevant signs and symptoms. Their outcomes were very good, with 84% achieving a successful outcome and only 9% not responding; 14% suffered a reoccurrence of symptoms at intervals ranging from two months to twelve years. These authors state:

“Manipulation of the spine can be effective treatment for lumbar disc protrusions.”

“Most protruded discs may be manipulated. When the diagnosis is in doubt, gentle force should be used at first as a trial in order to gain the confidence of the patient.”

“During manipulation a snap may accompany rotation. Subjectively it has dramatic influence on both patient and operator and is thought to be a sign of relief.”

“If derangement of the facets or subluxation of the posterior elements near the protruded disc occurs, the rotation may have caused reduction, giving remarkable relief.”

“Gapping of the disc on bending and rotation may create a condition favorable for the possible reentry of the protruded disc into the intervertebral cavity, or the rotary manipulation may cause the protruded disc to shift away from pressing on the nerve root.”

•••••••••

In 1989, a study was published, titled (22):

Lumbar Intervertebral Disc Herniation:

Treatment by Rotational Manipulation

This was a case study of a patient with an “enormous central herniation lumbar disc” who underwent a course of side posture manipulation. The patient improved considerably with only 2 weeks of treatment. The authors state:

“It is emphasized that manipulation has been shown to be an effective treatment for some patients with lumbar disc herniations.”

•••••••••

In 1993, a “review of the literature” study was published, titled (23):

Side Posture Manipulation for Lumbar Intervertebral Disk Herniation

These authors state:

“The treatment of lumbar disk herniation by side posture manipulation is not new and has been advocated by both chiropractors and medical manipulators.”

“The treatment of lumbar intervertebral disk herniation by side posture manipulation is both safe and effective.”

•••••••••

In 1995, a study was published, titled (24):

A Series of Consecutive Cases of Low Back Pain

with Radiating Leg Pain Treated by Chiropractors

The authors retrospectively reviewed the outcomes of 59 consecutive patients complaining of low back and radiating leg pain were clinically diagnosed as having a lumbar spine disk herniation. Ninety percent of these patients reported improvement of their complaint after chiropractic manipulation. The authors concluded:

“Based on our results, we postulate that a course of non-operative treatment including manipulation may be effective and safe for the treatment of back and radiating leg pain.”

•••••••••

In 2006, a study was published, titled (25):

Chiropractic Manipulation in the Treatment

of Acute Back Pain and Sciatica with Disc Protrusion

The purpose of this study was to assess the short- and long-term effects of spinal manipulations on acute back pain and sciatica with disc protrusion. It is a randomized double-blind trial comparing active and simulated manipulations for these patients. The study used 102 patients. The manipulations or simulated manipulations were done 5 days per week by experienced chiropractors for up to a maximum of 20 patient visits, “using a rapid thrust technique.” Re-evaluations were done at 15, 30, 45, 90, and 180 days. The authors made these observations:

“Active manipulations have more effect than simulated manipulations on pain relief for acute back pain and sciatica with disc protrusion.”

“At the end of follow-up, a significant difference was present between active and simulated manipulations in the percentage of cases becoming pain-free (local pain 28% vs. 6%; radiating pain 55% vs. 20%).”

“Patients receiving active manipulations enjoyed significantly greater relief of local and radiating acute LBP, spent fewer days with moderate-to-severe pain, and consumed fewer drugs for the control of pain.”

The authors concluded that chiropractic spinal “manipulations may relieve acute back pain and sciatica with disc protrusion.”

••••••••

In 2010, a study was published, titled (26):

Manipulation or Micro-Diskectomy for Sciatica?

The purpose of this study was to compare the clinical efficacy of spinal manipulation against micro-diskectomy in patients with sciatica secondary to lumbar disk herniation. It is a randomized clinical trial. All study subjects suffered from sciatic radiculopathy for more than 3 months.

All study subjects were referred for neurosurgery by their primary care physician after they failed at least 3 months of conservative management including treatment with analgesics, lifestyle modification, physiotherapy, massage therapy, and/or acupuncture. After failing 3 months of traditional conservative care (analgesics, lifestyle modification, physiotherapy, massage, and/or acupuncture), 40 patients were randomized to either surgical micro-diskectomy or to chiropractic spinal manipulation.

At the 12-week follow-up, 60% of the manipulation group “demonstrated clear improvement in outcomes and continued to complete the 52-week follow-up period.” The authors state:

“Although 40% of patients referred to spinal manipulative therapy for lumbar disc herniation-induced sciatica may fail to achieve satisfactory relief, the obvious risk and cost profile of operative care argues for serious physician and patient consideration of spinal manipulative therapy before surgical intervention.”

•••••••••

In 2014, an interdisciplinary group of physicians, chiropractors, and researchers published a study titled (27):

Spinal Manipulation and Home Exercise with Advice

for Subacute and Chronic Back-Related Leg Pain

This study included 192 patients who were suffering from back-related leg pain for at least 4 weeks. The authors concluded:

“For leg pain, spinal manipulative therapy plus home exercise and advice had a clinically important advantage over home exercise and advice at 12 weeks.”

“For patients with subacute and chronic back-related leg pain, spinal manipulative therapy in addition to home exercise and advice is a safe and effective conservative treatment approach, resulting in better short-term outcomes than home exercise and advice alone.”

•••••••••

Also in a 2014 study, a group of multidisciplinary researchers and chiropractic clinicians presented a prospective study involving 148 patients with low back and leg pain, titled (28):

Outcomes of Acute and Chronic Patients with Magnetic Resonance Imaging–Confirmed Symptomatic Lumbar Disc Herniations Receiving High-Velocity, Low-Amplitude, Spinal Manipulative Therapy

The purpose of this study was to document outcomes of patients with confirmed, symptomatic lumbar disc herniations and sciatica that were treated with chiropractic side posture high-velocity, low-amplitude, spinal manipulation to the level of the disc herniation. The authors made the following statements:

“The proportion of patients reporting clinically relevant improvement in this current study is surprisingly good, with nearly 70% of patients improved as early as 2 weeks after the start of treatment. By 3 months, this figure was up to 90.5% and then stabilized at 6 months and 1 year.”

“A large percentage of acute and importantly chronic lumbar disc herniation patients treated with chiropractic spinal manipulation reported clinically relevant improvement.”

“A large percentage of acute and importantly chronic lumbar disc herniation patients treated with high-velocity, low-amplitude side posture spinal manipulative therapy reported clinically relevant ‘improvement’ with no serious adverse events.”

“Spinal Manipulative therapy is a very safe and cost-effective option for treating symptomatic lumbar disc herniation.”

•••••••••

In 2021, a study was published, titled (29):

Physical Therapy Referral from Primary Care

for Acute Back Pain With Sciatica

This study involved 220 subjects with an acute onset of low back pain and sciatica. Half were given usual care (drugs and a single education session), and half were referred for 6-8 early sessions of exercise with mechanical manual therapy. The manual therapy consisted of mobilization or high-velocity thrust manipulation of the lumbar spine. The authors noted:

“Patients receiving [early mechanical treatment] were more likely to rate their treatment as successful at 4 weeks and 1 year.”

Early treatment “hastened functional improvement, indicating that [early mechanical treatment] can be offered to patients as first-line nonpharmacologic care.”

Early mechanical treatment “for recent-onset low back pain and sciatica resulted in greater improvement in disability and secondary outcomes than usual care across the 1-year follow-up.”

••••••••

Also in 2021, a study was published, titled (30):

Spinal Manipulation for Subacute and Chronic Lumbar Radiculopathy

The objective of this study was to evaluate the efficacy of spinal manipulation for the management of subacute and/or chronic lumbar radiculopathy. Forty-four patients, with unilateral radicular low back pain lasting more than 4 weeks, were randomly allocated to a treatment group [manipulation + physiotherapy] and a control group [physiotherapy only]. Key points from the authors include:

“Spinal manipulation improves the results of physiotherapy over a period of 3 months for patients with subacute or chronic lumbar radiculopathy.”

“Minimum side effects, ease of administration, and patient satisfaction are the expected benefits of manipulation.”

•••••••••

Conclusions

It is understood that some patients suffering from discogenic compressive radicular sciatica will require some form of decompressive spinal surgery. The studies presented here support that prior to surgery, spinal manipulation should be tried in an effort to avoid surgery. Spinal manipulation, especially by those expertly trained (chiropractors), is safe and often very effective. Chiropractors are also trained to monitor patient progress for any symptoms or signs that might benefit from a surgical consultation.

REFERENCES

- Wang S; Why Does Chronic Pain Hurt Some People More?; Wall Street Journal; October 7, 2013.

- Fritz JM, Lane E, McFadden M, Brennan G, Magel JS, Thackeray A, Minick K, Meier W, Greene T; Physical Therapy Referral from Primary Care for Acute Back Pain with Sciatica: A Randomized Controlled Trial; Annals of Internal Medicine; January 2021; Vol. 174; No. 1; pp. 8-17.

- Nachemson A; The Lumbar Spine, An Orthopedic Challenge; Spine; Vol. 1; No. 1; March 1976; pp. 59-71.

- Kuslich S, Ulstrom C, Michael C; The Tissue Origin of Low Back Pain and Sciatica: A Report of Pain Response to Tissue Stimulation During Operations on the Lumbar Spine Using Local Anesthesia; Orthopedic Clinics of North America; Vol. 22; No. 2; April 1991; pp. 181-187.

- Izzo R, Popolizio T, D’Aprile P, Muto M; Spine Pain; European Journal of Radiology; May 2015; Vol. 84; pp. 746–756.

- McGowan JR, Suiter L; Cost-Efficiency and Effectiveness of Including Doctors of Chiropractic to Offer Treatment Under Medicaid: A Critical Appraisal of Missouri Inclusion of Chiropractic Under Missouri Medicaid; Journal of Chiropractic Humanities; December 2019; Vol. 10; No. 26; pp. 31-52.

- Adams J, Peng W, Cramer H, Sundberg T, Moore C; The Prevalence, Patterns, and Predictors of Chiropractic Use Among US Adults: Results From the 2012 National Health Interview Survey; Spine; December 1, 2017; Vol. 42; No. 23; pp. 1810–1816.

- Kirkaldy-Willis WH, Cassidy JD; Spinal Manipulation in the Treatment of Low back Pain; Canadian Family Physician; March 1985; Vol. 31; pp. 535-540.

- Meade TW, Dyer S, Browne W, Townsend J, Frank OA; Low back pain of mechanical origin: Randomized comparison of chiropractic and hospital outpatient treatment; British Medical Journal; June 2, 1990; Vol. 300; pp. 1431-1437.

- The Lancet; Chiropractors and Low Back Pain; July 28, 1990; p. 220.

- Giles LGF; Muller R; Chronic Spinal Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial Comparing Medication, Acupuncture, and Spinal Manipulation; Spine; July 15, 2003; Vol. 28; No. 14; pp. 1490-1502.

- Muller R, Giles LGF; Long-Term Follow-up of a Randomized Clinical Trial Assessing the Efficacy of Medication, Acupuncture, and Spinal Manipulation for Chronic Mechanical Spinal Pain Syndromes; Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics; January 2005; Vol. 28; No. 1; pp. 3-11.

- Kellgren JH, Lewis; Observations on referred pain arising from muscle; Clinical Science; 1938; Vol. 3; p. 175.

- Kellgren JH; On the distribution of pain arising from deep somatic structures with charts of segmental pain areas; Clinical Science; 1939; Vol. 4; pp. 35-46.

- Hicks BL, Lam JC, Varacallo M; Piriformis Syndrome; StatPearls [Internet]; Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; January 2022.

- Ramsey RH; Conservative Treatment of Intervertebral Disk Lesions; American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons; Instructional Course Lectures; Vol. 11; 1954; pp. 118-120.

- Mathews JA and Yates DAH; Reduction of Lumbar Disc Prolapse by Manipulation; British Medical Journal; September 20, 1969; No. 3; pp. 696-697.

- Edwards BC; Low back pain and pain resulting from lumbar spine conditions: a comparison of treatment results; Australian Journal of Physiotherapy; September 1969; Vol. 15; No. 3; pp. 104-110.

- White AA, Panjabi MM; Clinical Biomechanics of the Spine; Second edition; JB Lippincott Company; 1990.

- Turek S; Orthopaedics, Principles and Their Applications; JB Lippincott Company; 1977; page 1335.

- Kuo PP, Loh ZC; Treatment of Lumbar Intervertebral Disc Protrusions by Manipulation; Clinical Orthopedics and Related Research; February 1987; No. 215; pp. 47-55.

- Quon JA, Cassidy JD, O’Connor SM, Kirkaldy-Willis WH; Lumbar intervertebral disc herniation: treatment by rotational manipulation; Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics; June 1989; Vol. 12; No. 3; pp. 220-227.

- Cassidy JD, Thiel HW, Kirkaldy-Willis WH; Side posture manipulation for lumbar intervertebral disk herniation; Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics; February 1993; Vol. 16; No. 2; pp. 96-103.

- Stern PJ, Côté P, Cassidy JD; A series of consecutive cases of low back pain with radiating leg pain treated by chiropractors; Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics; Jul-Aug 1995; Vol. 18; No. 6; pp. 335-342.

- Santilli V, Beghi E, Finucci S; Chiropractic manipulation in the treatment of acute back pain and sciatica with disc protrusion: A randomized double-blind clinical trial of active and simulated spinal manipulations; The Spine Journal; March-April 2006; Vol. 6; No. 2; pp. 131–137.

- McMorland G, Suter E, Casha S, du Plessis SJ, Hurlbert RJ; Manipulation or Microdiskectomy for Sciatica? A Prospective Randomized Clinical Study; Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics; October 2010; Vol. 33; No. 8; pp. 576-584.

- Bronfort G, Hondras M, Schulz CA, Evans RL, Long CR, Grimm R; Spinal Manipulation and Home Exercise With Advice for Subacute and Chronic Back-Related Leg Pain: A Trial With Adaptive Allocation; Annals of Internal Medicine; September 16, 2014; Vol. 161; No. 6; pp. 381-391.

- Leemann S, Peterson CK, Schmid C, Anklin B, Humphreys BK; Outcomes of Acute and Chronic Patients with Magnetic Resonance Imaging–Confirmed Symptomatic Lumbar Disc Herniations Receiving High-Velocity, Low Amplitude, Spinal Manipulative Therapy: A Prospective Observational Cohort Study With One-Year Follow-Up; Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics; March/April 2014; Vol. 37; No. 3; pp. 155-163.

- Fritz JM, Lane E, McFadden M, Brennan G, Magel JS, Thackeray A, Minick K, Meier W, Greene T; Physical Therapy Referral from Primary Care for Acute Back Pain with Sciatica: A Randomized Controlled Trial; Annals of Internal Medicine; January 2021; Vol. 174; No. 1; pp. 8-17.

- Ghasabmahaleh SH, Rezasoltani Z, Dadarkhah A, Hamidipanah S, Mofrad RK, Sharif Najafi S; Spinal Manipulation for Subacute and Chronic Lumbar Radiculopathy: A Randomized Controlled Trial; The American Journal of Medicine; January 2021; Vol. 134; No. 1; pp. 135−141.

“Authored by Dan Murphy, D.C.. Published by ChiroTrust® – This publication is not meant to offer treatment advice or protocols. Cited material is not necessarily the opinion of the author or publisher.”