Cervical Angina and Chiropractic Care

The Important Diagnostic Contributions of R. Glen Spurling, MD

Default Thinking

The 1989 movie “The War of the Roses” starred Kathleen Turner and Michael Douglas. In the movie, there is a scene at a restaurant where character Oliver Rose, played by actor Michael Douglas, has an episode of chest pain. The immediate suspicion by Mr. Rose and other restaurant patrons is that he is having a heart attack. An ambulance is called and he is taken to the hospital. His medical diagnosis was that he was suffering from a hiatal hernia.

The United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) notes that the primary cause in death in the United States is heart disease (1). The most recent statistic is 695,547 deaths per year (1). It makes sense that an episode of combinations of chest pain, shoulder pain, arm pain, jaw pain, upper back pain, and/or neck pain would be concerning for cardiac involvement. Yet, only 15% to 25% of patients with acute chest pain will actually have acute coronary syndrome (2).

Chiropractors manage neuromusculoskeletal syndromes, and they are good at it (3). Ninety-three percent of chiropractic patients present with neck and/or low back spinal pain complaints (3). Yet, it is important to know that the same cervical (neck) and thoracic (mid-back) spinal nerves that send pain signals to the brain also innervate the chest, shoulder, and arm. Conceptually, symptoms that may initially be interpreted as being a heart problem may in fact be a neuromusculoskeletal pain syndrome.

Roy Glenwood Spurling, MD

1894-1968

Roy Glenwood Spurling, MD, spent most of his career as a neurosurgeon in Louisville, Kentucky. He was a 1923 graduate from Harvard Medical School. He was a founding member and a president of the American Association of Neurological Surgeons in 1931. During World War II, he was the first Chief of Neurosurgery at Walter Reed Hospital, and he organized the neurosurgical service for the United States Army. In 1944, he was posted as a neurosurgeon in London. During the War, Dr. Spurling achieved the U.S. Army rank of Lieutenant Colonel.

In 2002, the Journal of Neurosurgery published an article titled (4):

Glen Spurling: Surgeon, Author, and Neurosurgical Visionary

The abstract from this article states:

“Doctor Roy Glenwood Spurling (1894-1968) stands as a prominent figure in the field of neurosurgery. His innovative contributions have left an indelible mark, particularly in the treatment of lumbar and cervical intervertebral disc diseases and peripheral nerve injuries. He was instrumental in founding the Harvey Cushing Society (later renamed the American Association of Neurological Surgeons) and the American Board of Neurological Surgery. Spurling was a major participant in the military during World War II; he was stationed at Walter Reed Hospital and in the European Theater, and later became well known for his care of General George S. Patton. Glen Spurling is a role model to a younger generation of neurosurgeons for his tireless effort toward the advancement of neurosurgery.”

In 1944, while serving in the Army, Lieutenant Colonel Spurling published an article in the journal Surgery, Gynecology and Obstetrics, titled (5):

Lateral Rupture of the Cervical Intervertebral Discs:

A Common Cause of Shoulder and Arm Pain

In this publication, Dr. Spurling described a test for the identification of cervical spine nerve roots in the pathogenesis of shoulder and arm pain. The test is based on the anatomical knowledge that cervical spine intervertebral foramina are narrowed in size during lateral flexion; cervical spine intervertebral foramina are further narrowed with ipsilateral (same side) rotation; and lastly, cervical spine intervertebral foramina are narrowed in size during compression that is applied to the top of the head. Hence, the combination of maximum cervical spine lateral flexion, maximum ipsilateral cervical spine rotation, and then the application of downward head compression will aggravate and elicit signs and symptoms of cervical spine radiculopathy.

Today, this test is universally known as Spurling’s Test.

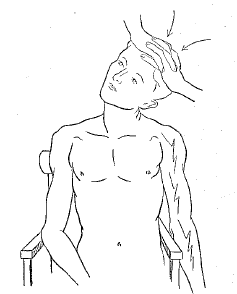

The original publication from 1944 has this drawing of Spurling’s Test (5):

After the War, in 1947, Dr. Spurling further described Spurling’s Test in the Journal of the International College of Surgery, in an article titled (6):

Rupture of the Cervical Intervertebral Disks

In this publication, Spurling writes:

“The most important diagnostic test and one that is almost pathognomonic of a cervical intraspinal lesion is the neck compression test. Tilting the head and neck toward the painful side may be sufficient to reproduce the characteristic pain and radicular features of the lesion. Pressure on the top of the head in this position may greatly intensify the symptoms. Tilting the head away from the lesion usually gives relief.”

In 1990, the second edition of the pioneering reference text Clinical Biomechanics of the Spine was published (7). The authors, Augustus White, MD, from Harvard, and Manohar Panjabi, PhD, from Yale, instantly became the global standard bearers for clinical biomechanics.

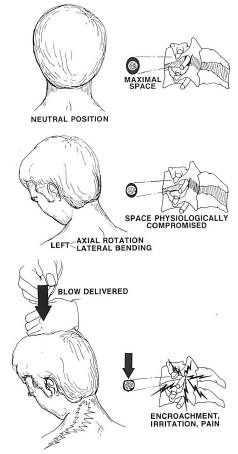

In their reference text they describe Spurling’s test, but with a slight modification (7).

They state:

“Spurling’s test is based on several biomechanical factors. If there is some pathological compromise or irritation of the nerve root, when the root passes through the intervertebral foramen the irritation is aggravated. In order to demonstrate this, the head is positioned as shown, and the coupled motions of axial rotation and lateral bending will further compromise the space available in the foramen. When the test is positive, a vertically directed blow of moderate impact produces an additional lateral bending moment that reduces this space, irritates the nerve root, and causes some combination of neck, shoulder, or arm pain. This does not occur in a normal person.”

Despite the prestige of the publication, most clinicians forgo the “blow” to the head, believing that it is excessive. Mild to moderate progressive pressure, as originally described by Dr. Spurling, is sufficient.

In 2012, a study was published in the Journal of Neuroimaging, titled (8):

The Correlation Between Spurling Test and Imaging Studies in Detecting Cervical Radiculopathy

The authors referred 257 patients with a positive Spurling test to CT and/or MRI imaging studies. They concluded:

“Sensitivity of the Spurling test to nerve root pathology was 95% and specificity was 94%.”

“This paper demonstrates that patients with positive Spurling test have probable nerve root pressure and should be sent for further imaging studies.”

•••••••••

The American Heart Association defines angina as (9):

“Angina is chest pain or discomfort caused when your heart muscle doesn’t get enough oxygen-rich blood. It may feel like pressure or squeezing in your chest. The discomfort also can occur in your shoulders, arms, neck, jaw, abdomen or back.”

“Angina” is a symptom, not a diagnosis. An established cause of “angina” is mechanical problems of the cervical spine (neck). Cervical spine etiology of angina is called “cervical angina.”

A literature search of the United States National Library of Medicine using the terms “cervical angina” identifies 580 studies (as of May 3, 2023).

To make a distinction, a number of publications term “cervical angina” as “pseudoangina.” A literature search of the United States National Library of Medicine using the terms “pseudoangina” identifies 56 studies (as of May 3, 2023).

••••

An early study pertaining to cervical angina was published in the Journal of the American Medical Association in 1934 by I. William Nachlas, MD. The article was titled (10):

Pseudo-angina Pectoris Originating in the Cervical Spine

Dr. Nachlas states:

“Angina pectoris is a disease characterized primarily by subjective clinical phenomena. There is pain in the left side of the chest, occasionally with radiation of pain down the left arm.”

Dr. Nachlas then describes three patients complaining of left-sided chest pain with left arm radiation. All three had been diagnosed with heart disease; one patient was also suspected of having left breast disease.

Failure to find evidence of heart or breast disease led to radiographic examination which showed arthritic changes of the lower cervical spine. Orthopedic examination showed corresponding joint pain. Dr. Nachlas noted:

“The common denominator in these three patients is an involvement of the lower cervical spine associated with thoracic pain.”

All three patients obtained complete resolution of their symptoms following mechanically based care.

••••

In 1990, Jules Constant, MD, from the Department of Internal Medicine, State University of New York at Buffalo, published an article in the Keio Journal of Medicine, titled (11):

The Diagnosis of Nonanginal Chest Pain

In this publication, Dr. Constant suggests that the following features may help distinguish primary heart problems versus non-cardiac causes of chest/arm pain. These include the understanding that primary heart disease:

- Very rarely elicits continuous pain for more than 30 minutes.

- Very rarely will have a pain duration of less than 5 seconds.

- Rarely increases with deep inspiration.

- Rarely is brought on by movement of the trunk or arm.

- Is not aggravated with digital palpation/pressure.

- Is not relieved by immediately lying down.

- The pain is not relieved within a few seconds of swallowing water or food.

- “It is well known that visceral pain is difficult to localize.” If the patient can localize the pain with one finger it is not likely to be cardiac; true cardiac pain is localized using the entire hand.

••••

In 2015, osteopathic and medical physicians from Saint Vincent Hospital and Worcester Medical Center, Worcester, MA, published a study in the journal Neurohospitalist, titled (12):

Cervical Angina:

An Overlooked Source of Noncardiac Chest Pain

The authors present a series of 6 cases of cervical angina that had presented to the Emergency Department with a suspected cardiac event, including this illustrative case:

- 50-year-old male with 1 month of neck pain radiating down his left arm, with associated tingling and weakness.

- Substernal chest pain.

- An extensive history of anginal symptoms, with associated left upper extremity radicular symptoms, extending back over 5.5 years.

- Three prior negative cardiac catheterizations and 2 negative stress tests.

- During this hospitalization, patients received a negative myocardial perfusion study and a negative cardiac catheterization, both revealing no evidence of coronary artery disease.

- A positive Spurling maneuver suggesting cervical radiculopathy.

- A cervical MRI showed neuroforaminal stenosis at left C4-5 and C5-6 levels.

- Electrodiagnostic studies were consistent with C5 and C6 radiculopathy.

The authors note that each year, more than 7 million patients present to emergency departments with chest pain. Yet, only 15% to 25% of these patients will actually have an acute coronary syndrome. The authors state:

“Cervical angina is one potential cause of noncardiac chest pain and originates from disorders of the cervical spine.”

“Cervical angina has been widely reported as a cause of chest pain but remains underrecognized.”

The authors further note that up to 70% of patients with cervical angina have cervical nerve root compression. The nerve roots involved are C4 to C8, which supply the sensory and motor innervation to the anterior chest wall through the medial and lateral pectoral nerves. The cause of the nerve root pathology is most often degenerative disk disease and/or facet joint pathology.

The most frequently affected levels are:

- C5-C6 37% of the time

- C6-C7 30% of the time

- C4-C5 27% of the time

- C3-C4 4% of the time

Interestingly, 50% to 60% of patients with cervical angina will experience sympathetic nervous system symptoms, such as dyspnea, vertigo, nausea, diaphoresis, pallor, fatigue, diplopia, and headaches.

In this study, the characteristics for these 6 patients who were diagnosed with cervical angina included:

- Three cases had left upper extremity pain or numbness.

- Three cases had symptoms of headaches, dizziness, and syncope.

- All six patients had cervical pathology on MRI. Four patients had cervical spondylotic radiculopathy or cervical disk disease causing neuroforaminal narrowing. Two patients had cervical myelopathy.

- All six patients had previously undergone cardiac stress testing or angiogram.

- During the present hospitalization, all patients had an electrocardiogram, chest x-ray, and cardiac enzymes tested, which were unremarkable.

- All coronary angiograms performed were normal.

- Features that increase suspicion for cervicogenic chest pain: “The Spurling maneuver, performed by rotating the cervical spine toward the symptomatic side while providing a downward compression through the patient’s head, has been shown to reproduce symptoms of cervical angina in case reports.” A positive Spurling maneuver correlates with findings on CT with a sensitivity of 95% and specificity of 94%.

The authors insist that cardiac causes of chest pain must be ruled out. This would involve, initially and at a minimum, electrocardiogram, chest x-ray, and cardiac enzymes. The authors state:

“Once coronary artery disease has been adequately excluded, cervical imaging can be helpful in defining anatomic abnormalities.”

“Plain radiographs or MRI may demonstrate degenerative cervical changes, including disk space narrowing, osteophyte formation, or neuroforaminal encroachment.”

“There should be a strong suspicion for cervical angina in any patient with inadequately explained noncardiac chest pain, especially, when neurologic signs and symptoms are present.”

“The majority of patients with cervical angina from cervical radiculopathy will respond to conservative care.”

“A greater awareness of this unusual radiating pattern for cervical pathology will hopefully lead to early diagnosis and a recognition that this symptom pattern is not due to dual clinical entities but unified by the diagnosis of cervical angina.”

The authors suggest the following history and physical examination findings as being useful in diagnosing cervical angina:

History

- History of cervical radiculopathy, upper extremity weakness or sensory changes, occipital headaches, or neck pain

- Pain induced by cervical range of motion or movement of the upper extremity

- History of cervical injury or recent history of manual labor (lifting, pulling or pushing, such as with yard work or lifting heavy objects)

- Pain persisting for >30 minutes or < than 5 seconds

Examination

- Restricted cervical motion and/or paraspinal tenderness

- Positive Spurling maneuver

- Radicular symptoms associated with a specific dermatome or myotome

- Radiological evidence of degenerative changes in the cervical spine

- Negative cardiac workup

Importantly, these authors note that the best physical examination test to distinguish between cardiac angina and cervical angina is Spurling’s Test.

••••

In 2022, a study was published in the Journal of Medical Cases, titled (13):

Cervical Radiculopathy as a Hidden Cause of Angina:

Cervicogenic Angina

The author, Dr. Chu, is a chiropractor. He presents a case of a 56-year-old man with non-traumatic chest pain and chronic neck pain for 2 years. The patient also had numbness in his right third and fourth fingers for 6 months.

An orthopedist diagnosed the patient with cervical radiculopathy and he was treated with analgesics and physical therapy. These treatments had only provided temporary improvement over a period of 6 months, so the patient sought chiropractic care.

Dr. Chu cites studies noting that 77% of the patients with chest pain symptoms presenting to the emergency department are not cardiac related.

He defines Cervicogenic Angina as an angina-like chest pain caused by cervical spine disorders. He states:

“Cervicogenic angina is defined as paroxysmal angina-like pain that originates from the disorders of the cervical spine or other neck structures.”

“Because cervicogenic angina mimics typical cardiac angina, symptoms in the elderly with cervical spondylosis are more frequently misdiagnosed.”

As a chiropractor, Dr. Chu notes “chiropractic care aims to alleviate neck pain, improve cervical alignment, restore cervical mobility, and prevent neurological damage.” His chiropractic examination findings on this case included:

- Restricted neck movement, a positive Spurling test, and hypoesthesia in the right C7 dermatome.

- Chest pain and numbness in the right fingers were both replicated by the Spurling compression test.

- Cervical x-rays showed degenerative spondylosis with right C5/C6 neuroforaminal stenosis and bilateral C6/C7 neuroforaminal stenosis.

Dr. Chu’s chiropractic care included high-velocity low-amplitude spinal manipulation to the dysfunctional joints of the cervical spine, soft tissue mobilization to treat the hypertonic muscles, and motorized intermittent neck traction. Initially, this care was performed three times per week. After the first month, care frequency was reduced to twice weekly.

The patient reported a 50% improvement in chest pain, neck pain, and radicular symptoms within the first 2 weeks of chiropractic care. After three months, the patient reported that the chest pain, neck pain, and radicular symptoms had completely resolved. The patient was able to discontinue all analgesic medicines. Long-term follow-up showed that the patient remains fully functional and pain free. Dr. Chu states:

“Cervicogenic angina is under recognized and appears to be neglected in ordinary clinical practice.”

“A growing body of evidence supports the application of manual therapy and exercise to treat mechanical neck pain like cervical radiculopathy.”

“In general, chiropractic therapy is regarded to be helpful in alleviating radiculopathy symptoms because it breaks up tissue adhesions, releases pinched nerve roots, and increases muscle strength and neck function.”

••••

A central theme in these studies is the importance of Spurling’s test in diagnosing cervicogenic angina.

All chiropractors see patients with cervical angina. They understand the necessity of clearing cardiac reasons for the patient’s symptoms. Once cleared, chiropractic care is exceptionally safe and effective for these patients.

REFERENCES

- https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/leading-causes-of-death.htm (accessed May 2, 2023).

- Pope JH, Aufderheide TP, Ruthazer R, Woolard RH, Feldman JA, Beshansky JR, Griffith JL, Selker H; Missed diagnoses of acute cardiac ischemia in the emergency department; New England Journal of Medicine; April 20, 2000; Vol. 342; No. 16; pp. 1163-1170.

- Adams J, Peng W, Cramer H, Sundberg T, Moore C; The Prevalence, Patterns, and Predictors of Chiropractic Use Among US Adults: Results From the 2012 National Health Interview Survey; Spine; December 1, 2017; Vol. 42; No. 23; pp. 1810–1816.

- Shields CB, Shields LBE; Glen Spurling: Surgeon, Author, and Neurosurgical Visionary; Journal of Neurosurgery; June 2002; Vol. 96; No. 6; pp. 1147-1153.

- Spurling RG, Scoville WB; Lateral Rupture of the Cervical Intervertebral Discs: A Common Cause of Shoulder and Arm Pain; Surgery, Gynecology and Obstetrics; April 1944; Vol. 78; No 4; pp. 350-358.

- Spurling RG; Rupture of the Cervical Intervertebral Disks; Journal of the International College of Surgery; Sept-Oct 1947; Vol. 10; No. 5; pp. 502-509.

- White AA, Panjabi MM; Clinical Biomechanics of the Spine; Second edition; JB Lippincott Company; 1990.

- Shabat S, Leitner Y, David R, Folman Y; The correlation between Spurling test and imaging studies in detecting cervical radiculopathy; Journal of Neuroimaging; October 2012; Vol. 22; No. 4; pp. 375-378.

- https://www.heart.org/en/health-topics/heart-attack/angina-chest-pain (accessed May 3, 2023).

- Nachlas IW; Pseudo-angina Pectoris Originating in the Cervical Spine; Journal of the American Medical Association; August 4, 1934; Vol. 103; No. 5; pp. 323-325.

- Constant J; The Diagnosis of Nonanginal Chest Pain; Keio Journal of Medicine; 1990; Vol. 39; No. 3; pp. 187-192.

- Sussman WI, Makovitch SA, Merchant SH, Phadke J; Cervical Angina: An Overlooked Source of Noncardiac Chest Pain; Neurohospitalist; January 2015; Vol. 5; No. 1; pp. 22-27.

- Chu ECP; Cervical Radiculopathy as a Hidden Cause of Angina: Cervicogenic Angina; Journal of Medical Cases; November 2022; Vol. 13; No. 11; pp. 545-550.