The Lumbar Discs, Low Back Pain,

and Chiropractic Care

A Simple Model

Approximately half of the adults in America suffer from chronic pain (1). Chronic pain affects every region of the body. The most significantly affected region of the body is the low back (2).

The largest modern review of the chiropractic profession was published in the journal Spine on December 1, 2017, and titled (3):

The Prevalence, Patterns, and Predictors

of Chiropractic Use Among US Adults

Results From the 2012 National Health Interview Survey

The data used in this study was from the National Health Interview Survey, which is the principal and reliable source of comprehensive health care information in the United States.

The authors note that there are more than 70,000 practicing chiropractors in the United States. Chiropractors use manual therapy to treat musculoskeletal and neurological disorders. The authors state:

“Chiropractic is one of the largest manual therapy professions in the United States and internationally.”

“Chiropractic is one of the commonly used complementary health approaches in the United States and internationally.”

“There is a growing trend of chiropractic use among US adults from 2002 to 2012.”

“Back pain (63.0%) and neck pain (30.2%) were the most prevalent health problems for chiropractic consultations and the majority of users reported chiropractic helping a great deal with their health problem and improving overall health or well-being.”

“A substantial proportion of US adults utilized chiropractic services during the past 12 months and reported associated positive outcomes for overall well-being…”

“Our analyses show that, among the US adult population, spinal pain and problems – specifically for back pain and neck pain – have positive associations with the use of chiropractic.”

“The most common complaints encountered by a chiropractor are back pain and neck pain and is in line with systematic reviews identifying emerging evidence on the efficacy of chiropractic for back pain and neck pain.”

“Chiropractic services are an important component of the healthcare provision for patients affected by musculoskeletal disorders (especially for back pain and neck pain) and/or for maintaining their overall well-being.”

Many clinical trials show that chiropractic care and spinal manipulation are safe and effective treatments for back pain (4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10). As a consequence, back pain clinical guidelines routinely advocate chiropractic care and spinal manipulation for the treatment of back pain (11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16).

•••••••••

Spinal joints bear weight. Weight-bearing joints commonly sustain wear-and-tear changes known as arthritis. The primary weight-bearing joints of the low back are the intervertebral disc (disc). Disc arthritic changes are often termed degenerative disc disease. Degenerative disc disease is often seen and diagnosed using spinal radiographs (x-rays).

Many healthcare providers, including many who specialize in the treatment of low back pain, attribute low back pain to spinal degenerative disc disease.

Intervertebral disc injury, abnormal stresses, excessive stresses, and/or prolonged normal stresses accelerate disc degradation. Once the disc matrix is degraded, normal activities of daily living may progressively accelerate the processes of disc degeneration.

Abnormal disc stresses and degradation generate an accumulation of inflammatory chemicals that depolarizes disc nociceptors (pain receptors). Chemical nociception sensitizes the nociceptors, rendering them more susceptible to mechanical stresses, increasing the perception of pain from mechanical events that otherwise would not be painful.

With advancing changes in the disc, crosslinking of collagen stiffens the disc matrix, often expressed clinically as a reduced range of movement. (5).

The resulting spinal stiffness allows the disc to further accumulate inflammatory nociceptive (pain) chemicals while adding to more abnormal cross-linking of the matrix collagen fibers. The positive feedback loop will not self-resolve and interventional help is required.

Canadian orthopedic surgeon William H. Kirkaldy-Willis, MD, offers a solution (5). He presented a series of 283 chronic, disabled, treatment resistant low back pain patients who were referred to a practicing chiropractor for spinal manipulation. The outcomes were exceptional. Essentially 81% of the patients recovered, especially those who were not suffering from compressive neuropathology.

Dr. Kirkaldy-Willis notes that in cases of chronic low back pain, there is a shortening of articular connective tissues, and intra-articular adhesions may form. Spinal manipulations can stretch or break these adhesions, restoring mobility. This approach may also remodel the abnormal disc matrix cross linkages (17).

••••

In 2004, a study was published in the journal Spine, titled (18):

Nutrition of the Intervertebral Disc

The authors, from Oxford University in the United Kingdom, summarized the information on disc nutrition in relation to intervertebral disc degeneration and disc degenerative disease.

The health of all body structures and tissues, including the intervertebral disc, is dependent upon the availability of nutrients. Intervertebral disc nutrition is more complicated than other structures in the body because the disc does not have a blood supply. The authors of this study state:

“The intervertebral disc is the largest avascular tissue in the body, and maintenance of an adequate nutrient supply has long been regarded as essential for preventing disc degeneration.”

“There is strong evidence that a fall in [disc] nutrient supply is associated with disc degeneration.”

“Disc cells require nutrients to stay alive and to function.”

The delivery of nutrients to the disc and the removal of metabolic waste products must rely on a mechanism other than direct blood flow.

Disc Nutrition from Vertebral Body Through End Plates

Above and below the avascular disc is the vertebral body. The vertebral body has an extensive blood supply. The nutrients in the vertebral body are allowed to pass through the porous cartilaginous end plates into the matrix of the intervertebral disc. This process is called diffusion.

Disc cellular health depends on diffusion through the cartilaginous end plates. Both nutrient delivery and the removal of metabolic wastes depends virtually entirely upon diffusion.

Things that interfere with disc diffusion reduce disc nutrient supply. Such things include:

- Sclerosis of the subchondral bone of the vertebral bodies adjacent to the cartilaginous end plates. This is caused by macro injury, repeated micro injury, or from chronic mechanical stresses. Chronic mechanical stress often results from excessive weight, excessive load (weight displaced by a lever arm), postural distortions, and/or alignment problems, including scoliosis. The authors state: “Calcification found in scoliotic discs can impede transport of even small molecules.”

- Calcification of the cartilaginous endplate. Once again, this is caused by macro injury, repeated micro injury, or from chronic mechanical stresses. The authors state: “Calcification of the endplate can act as a significant barrier to nutrient transport… Nutrients may not reach the disc cells if there is sclerosis of the subchondral bone or if the cartilaginous endplate calcifies.”

- Disorders that affect the blood supply to the vertebral body. Such issues include arterial disease including atherosclerosis. The authors state: “Disorders that affect the blood supply to the vertebral body such as atherosclerosis of the abdominal aorta are associated with disc degeneration and back pain.”

- Chronic exposure to vibration. This would include the operation of certain machinery/equipment and of long-haul vehicle driving (truckers).

- Smoking. Smoking constricts the microcirculation that supplies nutrients to the disc.

Key summary points from the authors include:

“The disc is avascular.”

“It is essential that the nutrient supply to the disc is adequate.”

“Essential nutrients are supplied to the disc virtually entirely by diffusion.”

“Loss of nutrient supply can lead to cell death, loss of matrix production, and increase in matrix degradation and hence to disc degeneration.”

“Injuries to the disc, sclerosis of the subchondral plate, and mechanical environment are all reported to affect the architecture of the capillary bed or the porosity of the subchondral plate with important consequences for delivery of nutrients to the disc.”

“Fluid movement in and out of the disc and the consequent changes in matrix properties could affect nutrient transport.”

“Failure of nutrient supply is thought to be a major cause of disc degeneration and a high proportion of degenerate discs do indeed appear to have an impaired nutrient supply.”

••••

In 2021, a study was published in the journal Pain Medicine, titled (19):

Innervation of the Human Intervertebral Disc:

The authors, from McGill University and the University of Western Ontario, provided a comprehensive systematic overview of studies that document the topography, morphology, and immunoreactivity of neural elements within the intervertebral disc in humans across the lifespan. It is a comprehensive review of the literature. All studies used were peer reviewed and used human tissues. The age of donors ranged from fetal and infant to adults over 80 years of age. Disc neural elements were studied with histology and immunohistochemistry.

To integrate the concept of disc innervation and back pain, the authors state:

“Back pain has a lifetime prevalence of 60–80% in the general population and is the leading cause of years lived with disability worldwide.”

“More than 85% of patients in the United States experience back pain for which an exact biological cause cannot be reliably identified.”

“The underlying pathology [for back pain] remains unknown in a significant number of cases.”

“Changes to the intervertebral disc (IVD) have been associated with back pain, leading many to postulate that the IVD may be a direct source of pain, typically referred to as discogenic back pain.”

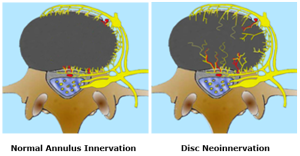

The authors restate that the intervertebral disc is the largest avascular tissue of the body. The disc has three distinct components:

- The central nucleus pulposus, which is rich in proteoglycans and water. “No neural elements were reported within the nucleus pulposus of control IVD tissues (32/33) across the lifespan, suggesting that it is a largely aneural structure in humans… Neural elements within the nucleus pulposus were identified in degenerated IVDs and/or those from patients reporting back pain… [The] nerve infiltration into the inner annulus fibrosus and/or nucleus pulposus was almost entirely limited to painful or degenerate IVDs.”

- The peripheral annulus fibrosus. “The annulus fibrosus was the most innervated tissue of the intervertebral disc, as neural elements were described in nearly all of the included articles (32/33).”

- The vertebral endplates. The endplate serves both to anchor the disc to the vertebra and acts as a permeable barrier for nutrient diffusion.

The authors note that nerves are consistently found within the outer layers of the annulus fibrosus. However, with disc disease and disc degeneration, nerve ingrowth into the inner annulus fibrosus and nucleus pulposus would occur. This is termed “neoinnervation.”

This neoinnervation of the intervertebral disc includes substantial nociceptive (pain producing) afferents. But pain perception requires more than nociceptive innervation. It also requires an environmental stressor to initiate the action potential process. Such an environmental stressor is nearly always inflammation (20).

Importantly, these authors also found an accumulation of pain initiating inflammatory chemicals in degenerated discs with neoinnervation.

The authors state:

“In adults, age-related degenerative changes or spine-related pathologies likely lead to increased infiltration of nerve fibers into the inner annulus fibrosus and nucleus pulposus of the IVD which continue to proliferate with increasing degeneration or disease severity.”

“It is clear that the human IVD is an innervated structure throughout life and that neural ingrowth is associated with the state of tissue degeneration or damage.”

The “changes to the IVD that occur with ageing, degeneration, and damage are associated with increased innervation of the IVD and may lead to discogenic back pain.”

•••••••••

It is often said, “the structure that produces pain must have a nerve supply.” Decades ago, the majority of studies, reference texts, instructors, and experts maintained that the intervertebral disc was without a nerve supply and hence could not be a source of back pain. It is now understood and accepted that:

- The disc is extensively innervated.

- With degenerative changes, the innervation of the disc increases, including innervation to the nucleus pulposus.

- Painful discs have more nerves as compared to nonpainful discs.

- Degenerating and diseased discs also accumulate inflammatory chemicals that depolarize disc nociceptors, initiating the perception of pain.

A SIMPLE CHIROPRACTIC MODEL

Chiropractors are primarily concerned about spinal motion and alignment integrity. Chiropractors refer to problems of spinal motion and alignment as the “subluxation.”

A subluxation, in part, reduces or alters segmental motion.

Reduced/altered motion impairs the nutrient diffusion through the porous cartilaginous end plate into the matrix of the intervertebral disc, to both the annulus fibrosis and the nucleus pulposus.

Impaired nutrient diffusion into the intervertebral disc enhances disc degeneration and degradation.

Intervertebral disc degeneration/degradation results in the accumulation of inflammatory chemicals. These inflammatory chemicals:

- Depolarize disc nociceptors, sending the pain signal to the brain.

- Accelerate the disc degeneration/degradation process, complicating recovery.

- Enhance disc “neoinnervation,” complicating recovery.

The chiropractic adjustment improves segmental motion. This improves disc nutrient diffusion and disperses accumulation of disc inflammatory chemicals, reducing disc nociception. This model is supported by the 1987 Presidential Address of the International Society for the Study of the Lumbar Spine by Vert Mooney, MD (21). Dr. Mooney’s Presidential Address was titled:

Where Is the Pain Coming From?

Dr. Mooney notes that “mechanical events can be translated into chemical events related to pain.” An important aspect of disc nutrition and health is the mechanical aspects of the disc related to the fluid mechanics.

The pumping action of the intervertebral disc maintains its nutrition and biomechanical function. Research substantiates that unchanging posture, as a result of constant pressure such as standing, sitting or lying, leads to an interruption of pressure-dependent transfer of liquid. The fluid content of the disc can be changed by mechanical activity. “Actually, the human intervertebral disc lives because of movement.” He states:

“In summary, what is the answer to the question of where is the pain coming from in the chronic low-back pain patient? I believe its source, ultimately, is in the disc. Basic studies and clinical experience suggest that mechanical therapy is the most rational approach to relief of this painful condition.”

“Prolonged rest and passive physical therapy modalities no longer have a place in the treatment of the chronic problem.”

Summary

Intervertebral disc injury and degeneration alter the disc matrix in such a way that inflammatory pain-producing chemicals accumulate. It is difficult for the disc to disperse these chemicals because the disc is avascular (has no blood supply). Chronic accumulation of inflammatory chemicals results in chronic low back pain.

Intervertebral disc injury and degeneration will attempt to heal by producing abnormal cross-links of collagen proteins. These abnormal cross-links further impair motion and the ability to disperse the accumulation of inflammatory chemicals.

Chiropractic adjustments (specific line-of-drive manipulations) can remodel the disc matrix and improve segmental motion. The improved motion activates a pumping mechanism (through the porous cartilaginous end-plates) that disperses the accumulated inflammatory chemicals. As stated by Dr. Vert Mooney above:

“Actually, the human intervertebral disc lives because of movement.”

The result is a unique approach for the management of low back pain that reduces pain and improves function.

REFERENCES:

- Foreman J; A Nation in Pain, Healing Our Biggest Health Problem; Oxford University Press; 2014.

- Wang S; Why Does Chronic Pain Hurt Some People More?; Wall Street Journal; October 7, 2013.

- Adams J, Peng W, Cramer H, Sundberg T, Moore C; The Prevalence, Patterns, and Predictors of Chiropractic Use Among US Adults; Results From the 2012 National Health Interview Survey; Spine; December 1, 2017; Vol. 42; No. 23; pp. 1810–1816.

- Kirkaldy-Willis WH; Managing Low Back Pain; Churchill Livingstone; 1983 and 1988.

- Kirkaldy-Willis WH, Cassidy JD; Spinal Manipulation in the Treatment of Low Back Pain; Canadian Family Physician; March 1985; Vol. 31; pp. 535-540.

- Meade TW, Dyer S, Browne W, Townsend J, Frank OA; Low back pain of mechanical origin: Randomized comparison of chiropractic and hospital outpatient treatment; British Medical Journal; Volume 300; June 2, 1990; pp. 1431-1437.

- Giles LGF, Muller R; Chronic Spinal Pain: A Randomized Clinical Trial Comparing Medication, Acupuncture, and Spinal Manipulation; Spine; July 15, 2003; Vol. 28; No. 14; pp. 1490-1502.

- Muller R, Lynton G.F. Giles LGF, DC, PhD; Long-Term Follow-up of a Randomized Clinical Trial Assessing the Efficacy of Medication, Acupuncture, and Spinal Manipulation for Chronic Mechanical Spinal Pain Syndromes; Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics; January 2005; Vol. 28; No. 1; pp. 3-11.

- Cifuentes M, Willetts J, Wasiak R; Health Maintenance Care in Work-Related Low Back Pain and Its Association With Disability Recurrence; Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine; April 14, 2011; Vol. 53; No. 4; pp. 396-404.

- Senna MK, Machaly SA; Does Maintained Spinal Manipulation Therapy for Chronic Nonspecific Low Back Pain Result in Better Long-Term Outcome? Randomized Trial; SPINE; August 15, 2011; Vol. 36; No. 18; pp. 1427–1437.

- Chou R, Qaseem A, Snow V, Casey D, Cross JT, Shekell, Owens DK; Diagnosis and Treatment of Low Back Pain; Annals of Internal Medicine; Vol. 147; No. 7; October 2007; pp. 478-491.

- Chou R, Huffman LH; Non-pharmacologic Therapies for Acute and Chronic Low Back Pain; Annals of Internal Medicine; October 2007; Vol. 147; No. 7; pp. 492-504.

- Globe G, Farabaugh RJ, Hawk C, Morris CE, Baker G, DC, Whalen WM, Walters S, Kaeser M, Dehen M, Augat T; Clinical Practice Guideline: Chiropractic Care for Low Back Pain; Journal of Manipulative and Physiological Therapeutics; January 2016; Vol. 39; No. 1; pp. 1-22.

- Wong JJ, Cote P, Sutton DA, Randhawa K, Yu H, Varatharajan S, Goldgrub R, Nordin M, Gross DP, Shearer HM, Carroll LJ, Stern PJ, Ameis A, Southerst D, Mior S, Stupar M, Varatharajan T, Taylor-Vaisey A; Clinical practice guidelines for the noninvasive management of low back pain: A systematic review by the Ontario Protocol for Traffic Injury Management (OPTIMa) Collaboration; European Journal of Pain; Vol. 21; No. 2; February 2017; pp. 201-216.

- Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, Forciea MA; Noninvasive Treatments for Acute, Subacute, and Chronic Low Back Pain: A Clinical Practice Guideline from the American College of Physicians; For the Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians; Annals of Internal Medicine; April 4, 2017; Vol. 166; No. 7; pp. 514-530.

- Oliveira CB, Maher CG, Pinto RZ, et al.; Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Non-Specific Low Back Pain in Primary Care: An Updated Overview; European Spine Journal; November 2018; Vol. 27; No. 11; pp. 2791-2803.

- Cyriax J; Textbook of Orthopaedic Medicine, Diagnosis of Soft Tissue Lesions; Bailliere Tindall; Vol. 1; Eighth edition; 1982.

- Urban JPG, Smith S, Fairbank JCT; Nutrition of the Intervertebral Disc; Spine; December 1, 2004; Vol. 29; No. 23; pp. 2700–2709.

- Groh AMR, Fournier DE, Battie MC, Seguin CA; Innervation of the Human Intervertebral Disc: A Scoping Review; Pain Medicine; June 4, 2021; Vol. 22; No. 6; pp. 1281–1304.

- Omoigui S; The Biochemical Origin of Pain: The Origin of All Pain is Inflammation and the Inflammatory Response: Inflammatory Profile of Pain Syndromes; Medical Hypothesis; 2007; Vol. 69; pp. 1169 – 1178.

- Mooney V; Where Is the Pain Coming From? Spine; October 1987; Vol. 12; No. 8; pp. 754-759.

“Authored by Dan Murphy, D.C.. Published by ChiroTrust® – This publication is not meant to offer treatment advice or protocols. Cited material is not necessarily the opinion of the author or publisher.”